Intersex: intersectionalities with lesbian and gay people

- Read more on intersex intersectionalities including with women, disabled people, and trans and gender diverse people

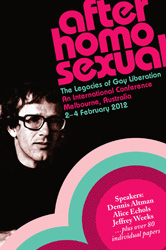

Morgan Carpenter, OII Australia board member, wrote and presented this paper at the After ‘Homosexual’ conference in Melbourne on 4 February 2012. The conference marked the fortieth anniversary of Dennis Altman’s book Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. The 10-minute presentation was delivered as part of a curated panel on intersectionalities.

Given the conference title, the focus is more on intersectionalities with people experiencing same-sex attraction. See this page for intersectionalities with trans experiences.

Introduction

I’d like to pay my respects to the indigenous owners of the land, and their elders past and present.

I’m speaking today as a member of OII Australia, a local intersex activist organisation that’s aligned with the LGBTI movement because of our common experience of homophobia, and misogyny. It’s clear at the conference that there’s no settled view on the inclusion of the ‘I’, so I’m going to present a few stories, mostly public ones, and a little history – to illuminate some of the intersections between intersex and the rest of the LGBTI communities.

Firstly, though, what is intersex?

Intersex is where a person’s biological sex is not clearly male or female; a person might have characteristics of both or neither. It’s always congenital. Someone can find out or be discovered to be intersex at birth, puberty, when trying to conceive a child, or serendipitously.

It’s not an identity: it’s not in our heads, although some of us will opt out of the gender binary. It’s typically carved into our bodies.

Two stories about heterosexuality

Hanne Blank, a fat activist and writer of a new history of heterosexuality called Straight was recently interviewed in Salon magazine. It reports:

While Blank looks like a feminine woman, her partner is extremely androgynous, with little to no facial hair and a fine smooth complexion. Hanne’s partner is neither fully male, nor fully female; he was born with an unconventional set of chromosomes, XXY, that provide him with both male genitalia and feminine characteristics. As a result, Blank’s partner has been mistaken for a gay woman, a straight man, a transman — and their relationship has been classified as gay, straight and everything in between.

Phoebe Hart is a young, married, Australian woman with male chromosomes and Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, which means that her body doesn’t respond to testosterone in a typical way. Her autobiographical movie, Orchids: My Intersex Adventure, screened on ABC1 last weekend and is still available on iView for another week. It has also screened during queer film festivals around the country and overseas.

About half an hour into the movie, she asks her husband, James, how he felt when she told him she was intersex. He says:

…once I found out what AIS was, I was confronted with the fact that I thought I might be gay myself. Genetically you’re a male! But I think you can fall in love with the person. Whether that person is male or female doesn’t really matter.

As a side note, I had a similar discussion with my then long-term male lover just after diagnosis, with a very different outcome.

Phoebe had internal testicles that produced testosterone. These were removed in adolescence due to a slight risk of cancer. What Phoebe doesn’t say in her movie is that risk is less than the cancer risk associated with having breasts. So why aren’t breasts routinely removed? The reason has to be that women are not supposed to have testicles. It’s a matter of shame, a secret.

But bodies need sex hormones, to mature, to maintain a libido, prevent osteoporosis and a host of other reasons. Removing her functional gonads means that she now needs lifelong hormone replacement treatment, with all the risks associated with that.

Medicalisation

Medicalisation goes back centuries, and for much of that time there was no clear differentiation between LGB, T and I.

Michel Foucault presented the case of Herculine Barbin, in nineteenth century France.

Mogul, Ritchie and Whitlock state:

Siobhan Somerville in Queering the Color Line reports “as late as 1921, medical journals contained articles declaring that a physical examination of [female homosexuals] will in practically every instance disclose an abnormally prominent clitoris” and that this is “particularly so in colored women”.

A key change happened in the 1950s, when New Zealand doctor John Money declared that sex equals nurture, not nature.

His (now discredited) work led to standard medical protocols that still result in cosmetic genital surgery on infants and children with intersex variations. Even now, in Australia, these are performed to prevent social and familial discomfort, despite medical research that shows poor satisfaction with surgery.

The trauma associated with these surgeries led to the establishment of an intersex movement, initially through a magazine advert and later online. The immediate priority of the movement, led by the Intersex Society of North America, was to engage with the medical profession, and this led in 2006 to a “consensus statement” that changed the terminology associated with intersex. It introduced the term “Disorders of Sex Development” or DSD.

The aim was to create a non-pejorative, value-neutral term to replace “intersex” and “hermaphrodite”. In a very literal sense it was homophobic: it aimed to eliminate a parental and social fear of homosexuality and queerness in an attempt to improve patient outcomes.

It failed.

Current rationales for infant genital surgery

The 2006 Consensus Statement on management of intersex itself describes the “rationale for early reconstruction” on infant genitals as including,

… minimizing family concern and distress, and mitigating the risks of stigmatization and gender-identity confusion…

Prenatal treatment to prevent homosexuality and masculinisation in CAH women

CAH, Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, is a manageable salt wasting condition that requires lifelong treatment. In women, it’s also associated with higher levels of prenatal testosterone, and a degree of physical and mental “masculinisation”.

In 1999, Columbia University psychologist Heino Meyer-Bahlburg published a paper entitled What Causes Low Rates of Child Bearing in CAH?:

CAH women as a group have a lower interest than controls in getting married and performing the traditional child-care/house-wife role. As children, they show an unusually low interest in engaging in… maternal play, motherhood…

Meyer-Bahlburg proposes that “treatment with prenatal dexamethasone might cause these girls’ behaviour to be closer to heterosexual norms”.

In an analysis that clearly shows the homophobic nature of these concerns, Alice Dreger tells how Meyer-Bahlburg and Dr Maria New of Mount Sinai School of Medicine in NY published research in 2008 stating:

Most women were heterosexual, but the rates of bisexual and homosexual orientation were increased above controls… and correlated with the degree of prenatal androgenization.

Dreger describes, in 2010, New and fellow pediatric endocrinologist Saroj Nimkarn (Weill Cornell Medical College) to be “constructing low interest in babies and men – and even interest in what they consider to be men’s occupations and games – as “abnormal,” and potentially preventable with prenatal dex”.

Dexamethasone is a class C steroid that, in tests on sheep, has been shown to result in reduced mental capacity. It’s also linked to low birth weight, a greater incidence of cleft palate and other issues.

Dr Maria New began clinical trials on pregnant human mothers in 2010 to reduce masculinisation effects on CAH girls.

Dexamethasone has no impact on the salt wasting associated with CAH.

Terminations

Genetic screening is now available for CAH and XXY, via amniocentesis. OII Australia is currently examining the effects of this in Australia, and preliminary research shows a drop in number of live births with these intersex variations.

Conclusions

The shift to DSD failed to change the system. It’s failed to change medical protocols.

It has also come close to destroying the intersex movement. We’ve had to start almost from scratch.

It is almost impossible for us to engage with the medical profession directly.

In many ways, the experience of intersex people shows what happens when a group of “disordered” people are found to be “born this way”.

Being trans remains a disorder, while no treatable biological cause has been established. Being gay or lesbian is no longer a disorder to doctors in most countries, even though this remains contentious in some major political and religious institutions.

The big weakness in the early intersex movement was a failure to organise around the causes of this medical treatment – homophobia, misogyny. We have to focus on the human rights and ethical case for liberation.

Intersex people are aligned with the “LGBTI” movement because of the nature of our oppression.

We seek the right to be ourselves as we are, in the context of infant and adolescent surgery, adult relationship and medical issues. Even “straight” intersex people and their partners have to question and address issues with their sexual orientation and gender identity.

We’ve been here all along, and we need to be included – especially in campaigns around health and social services practices and policies, employment protection, and other frameworks for our LGBTI communities.

Notes

1. OII Australia does not support the establishment of a third gender category, but does seek the ability for all adults to opt out of the gender binary and use neutral sex or gender markers on legal documents. For more on the 2003 and 2011 ‘X’ passport reforms see here.

2. Intersex is about an experience of the body, not identity. Nor is intersex synonymous with androgyny. Any person, intersex or otherwise, may feel more comfortable with a non-binary identity such as intergender, or genderqueer.

3. There are many more intersex variations than those mentioned in this presentation.

4. We reject pathologising language, such as “disorders”. Intersex variations are a natural part of the human condition.

5. With thanks to Gina Wilson, chairperson of OII Australia, Hida Viloria, chair of OII, and Gavriel Ansara for help during the researching of this paper. The article includes some minor changes post-delivery at the conference.

6. Republishing this presentation is subject to written consent on terms available by request. (Sharing the link is, of course, ok).

References:

- Alice Dreger, in Hastings Center Bioethics Forum, 29 June 2010: Preventing Homosexuality (and Uppity Women) in the Womb?

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation, January 2012: Orchids: My Intersex Adventure on iView

- Fetaldex.org, accessed 1 February 2012

- Michel Foucault: Herculine Barbin at Amazon.com

- Lydia Guterman, in Open Society Foundations, 30 January 2012: Why Are Doctors Still Performing Genital Surgery on Infants?

- Phoebe Hart, 2010: Orchids: My Intersex Adventure

- W. L. Huang et al in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol 94 issue 2, August 1999: Effect of Corticosteroids on Brain Growth in Fetal Sheep

- La Trobe University, 2011: After ‘Homosexual’ conference page

- Mogul, Ritchie and Whitlock, 15 February 2011: Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States (Queer Action / Queer Ideas) at Amazon.com

- OII Australia, 15 October 2009: Doctors Remove the Gonads of All Intersex Females with A.I.S. … Because

- OII Australia, 9 October 2011: The facts about the new policy on Australian passports’ X sex field designation

- OII Australia, 22 November 2011: Intersex people with AIS found to be dissatisfied with results of non-consensual genital surgery done upon them as newborns and infants

- Thomas Rogers, in Salon Magazine, 23 January 2012: The invention of the heterosexual interview with author Hanne Blank.

More information

This page is not intended as an introduction to intersex.

- We recommend our Intersex for allies leaflet as an introduction to intersex.

- Read more on intersex intersectionalities with other populations

- Defining intersex: Australian and international definitions.

- Resources listing – a curated list of key resources on the Intersex Human Rights Australia site.

You must be logged in to post a comment.