New publication “Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia”

“Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia” by Tiffany Jones, Bonnie Hart, Morgan Carpenter, Gavi Ansara, William Leonard, and Jayne Lucke

We announce that the 2015 survey of people born with atypical sex characteristics has now been published.

This survey was an independent research project led by Dr Tiffany Jones. The book has been peer reviewed and published by an academic publisher, Open Book Publishers. The strong team of co-authors includes a reference group of community representatives; researchers and academic experts in health and education, including experts in sexual and reproductive health, clinical research, women’s health and public health.

The report is available as a free PDF download. Paperback, hardback and e-book versions can also be purchased. We would like to thank Tiffany Jones, co-authors and reference group, survey participants, and the folks at Open Book Publishers.

Here is a quick summary of some key points:

- experience of medicalisation is often negative, with poor information, many poor outcomes, and “strong evidence suggesting a pattern of institutionalised shaming and coercive treatment”.

- rates of suicidality far exceed the average for Australia, including suicide attempts by 19% of respondents.

- education experiences are impacted by bullying and medical treatment that is coincident with puberty, with high rates of early school leaving.

- there are high rates of poverty: the majority of participants (63%) earned an income under AU$41,000 per year, 41% earn less than AU$20,000 per year (the minimum wage during the survey period was ~AU$34,158).

- “52% of the participants were allocated a female sex at birth, 41% male, 2% X, 2% unsure and 4% another option. Whilst most identified as female or male now, a smaller portion now identified as male compared to the portion assigned male at birth; and a greater portion now used X or another option”

- intersex is the only widespread popular term for atypical sex characteristics; “disorders of sex development” is markedly unpopular, used by 3% of respondents rising to 21% situationally, when accessing medical services.

- 48% of respondents were heterosexual, 10% asexual; a third of people use multiple labels to define their sexuality. A minority of participants identify as transgender.

- 27% of respondents have a disability, higher than the average for Australians.

- peer and social support from people with intersex traits is really important.

More information, including some quotations from the report and survey respondents, follow.

“This research survey was actually the best I have ever filled out. I liked the questions and even though some things were hard to talk about, it meant the world to me that finally there is somewhere I can talk about them and have my voice heard. I hope you do another one.”

(statement by respondent)

The survey was completed by 272 respondents, making this one of the largest studies of intersex people yet conducted, and it may be the first to investigate a broad range of issues, from how people see their own bodies, to experiences of health services, education, and employment.

We need to advise that personal stories comprise an essential element in this research, giving voice to the issues identified. Individuals may see their own words included, as disclosed in the survey documentation. Data were collected anonymously, and pseudonyms were assigned in the survey report.

Demographics

80% of respondents are Australian resident, and responses by local international respondents were not statistically different. Respondents came from all States and Territories, and 4% were Indigenous. Participants ranged in age from 16 to over 85 years of age. 27% have a disability (compared to 18.%% of the broader Australian population).

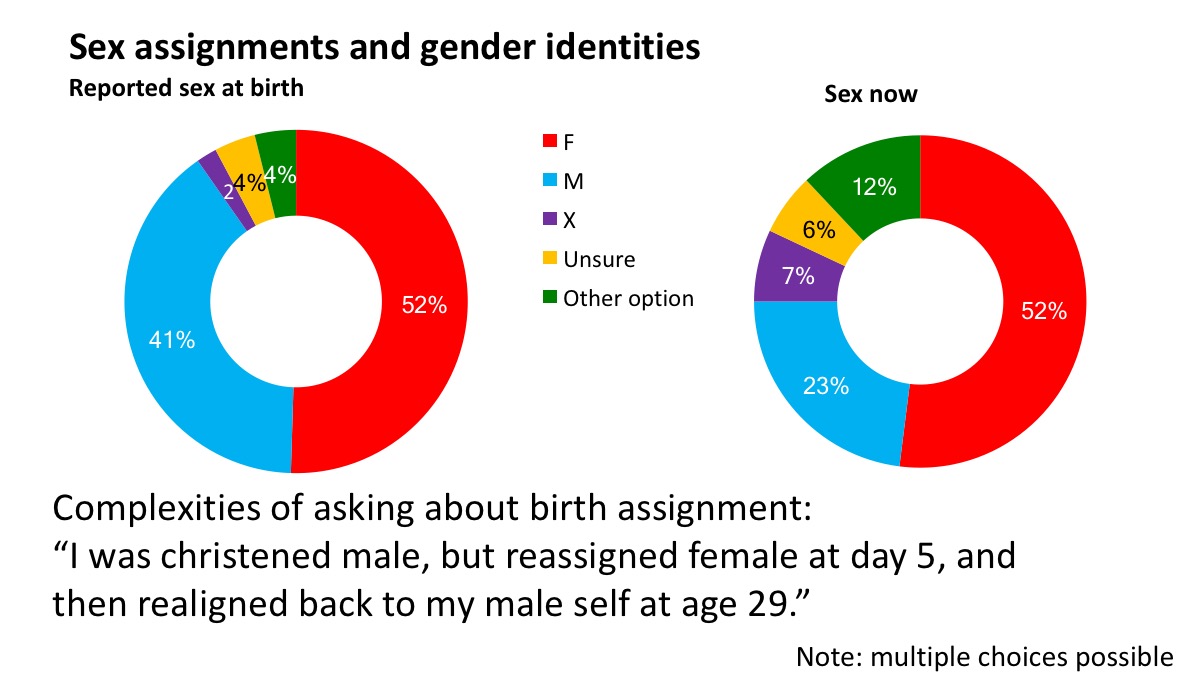

(Legal) sex assignments and gender identities

People born with atypical sex characteristics have many different sex assignments and gender identities:

Overall, 52% of the participants were allocated a female sex at birth, 41% male, 2% X, 2% unsure and 4% another option. Whilst most identified as female or male now, a smaller portion now identified as male compared to the portion assigned male at birth; and a greater portion now used X or another option.

This data demonstrate the complexity of assigning (and reporting) a legal sex at birth for people born with atypical sex characteristics. The “Sex now” data show personal identification at the time of the survey: 52% of respondents indicated that they were female, 23% indicated that they were male, and 25% selected a variety of other options. Multiple choices were possible.

It is clear that one single legal sex classification is not appropriate for all intersex people. It is also clear that we are more likely to reject the sex of rearing or be gender fluid than the general population. One quarter of respondents had sex markers or gender identities other than female or male. Conversely, 75% are female or male, and these classifications or identifications also need respect.

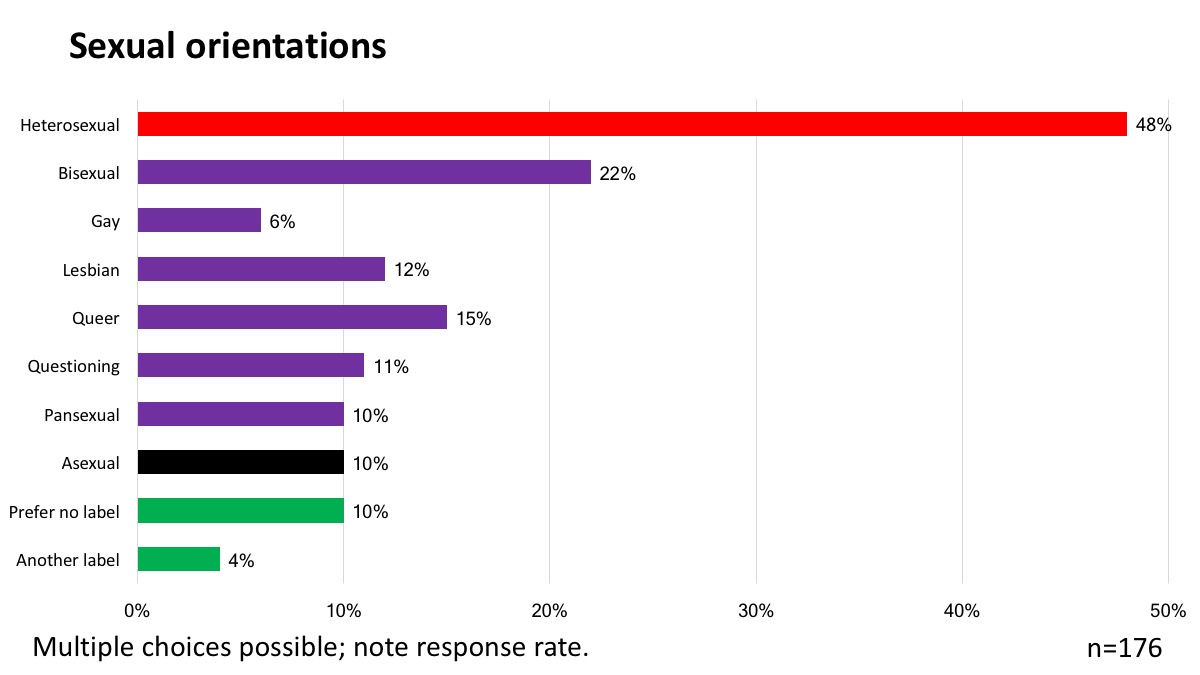

Sexual orientations

48% of respondents stated that they were heterosexual, while 22% selected bisexual, 15% queer. 10% of individuals stated asexual, while the same percentage “prefer no label” and 4% prefer “another label”. Multiple choices were possible.

The data shows that people born with atypical sex characteristics are more likely to be non-heterosexual than the general population, and we may also be more likely to be asexual.

Additionally, there is a clear need to recognise that many intersex people are heterosexual. As with transgender populations, this means that many “LGBTI” people are heterosexual. A minority of respondents identified as transgender.

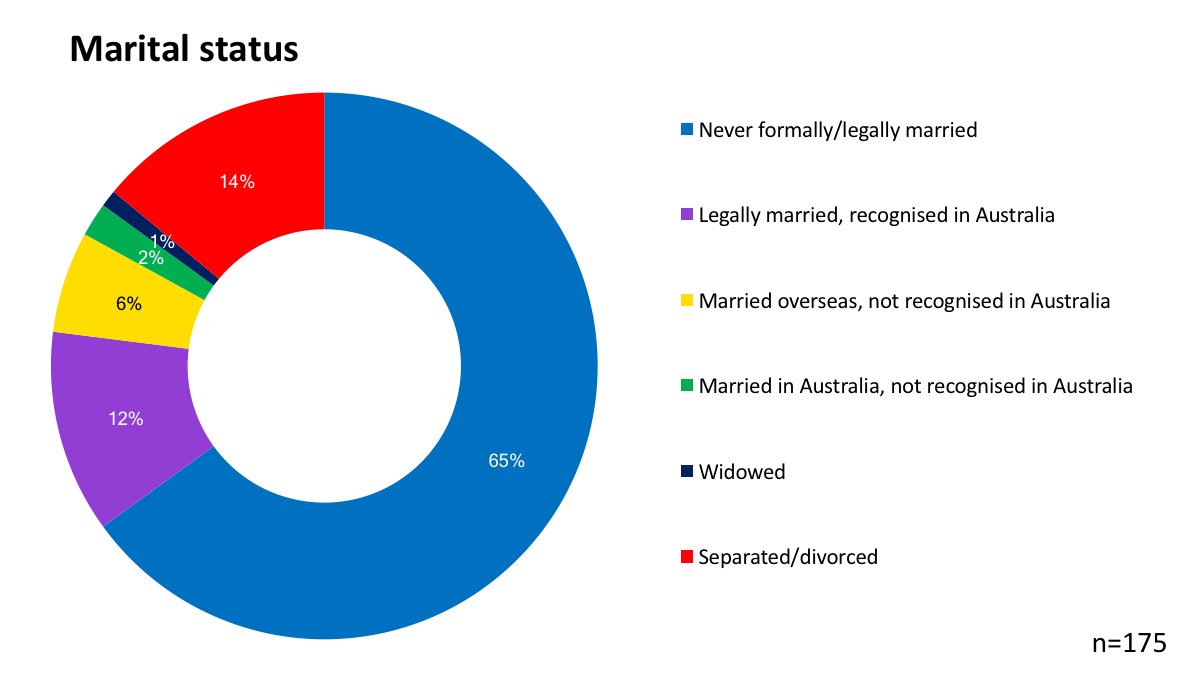

Marital status

65% of respondents who answered a question on marriage and relationships had never legally or formally married. 12% of respondents are legally recognised as married in Australia. 8% of people had married overseas (6%) or in Australia (2%) but their marriage is not recognised here. 1% were widowed, and 14% are separated or divorced.

Overall, 62% of respondents were in a relationship or dating. 65% of participants in the survey said that “their variation (or related treatments) impacted on their sexual activities”.

Atypical sex characteristics

- Participants had over 40 specific intersex variations, ranging from 5-ARDS to XY Turner’s Syndrome Mosaics.

- Most (64%) learned about their variation at under 18yrs, a third as adults; learning about a variation usually involved being told by doctors or parents.

- 22% knew they had relatives with their variation, usually more than one. These relatives were most often siblings.

Respondents had more than 35 different variations, including 5-alpha-reductase deficiency, complete and partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), bladder exstrophy, clitoromegaly, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), cryptorchidism, De la Chapelle (XX Male) syndrome, epispadias, Fraser syndrome, gonadal dysgenesis, hyperandrogenism with PCOS, hypospadias, Kallmann syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome/XXY, leydig cell hypoplasia, Mayer- Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH, mullerian agenesis, vaginal agenesis), micropenis, mosaicism involving sex chromosomes, mullerian (duct) aplasia, ovo-testes, progestin induced virilisation, Swyer syndrome, Turner’s syndrome/X0 (TS), Triple-X syndrome (XXX).

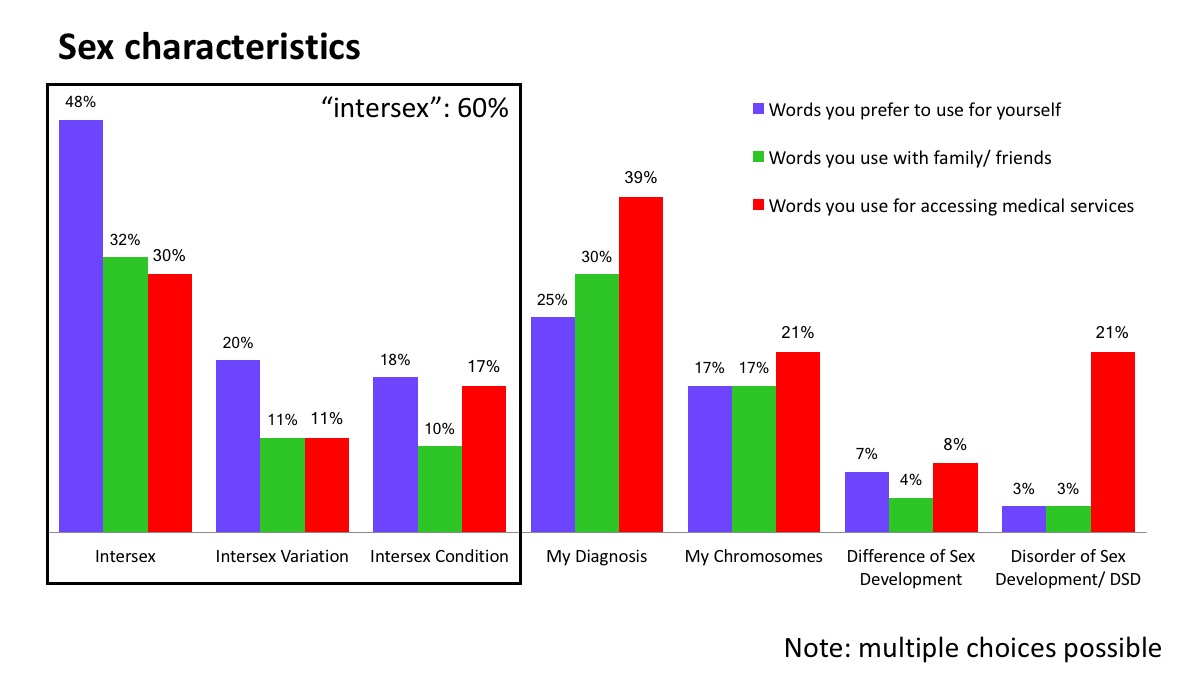

Words used to describe sex characteristics

The words people use to describe our bodies and sex characteristics vary significantly. The generic title of the research enabled an investigation into the words people use to describe their sex characteristics, and 60% use the word “intersex” in one form or another. A proportion describe as “having an intersex variation” or “having an intersex condition”. The use of diagnostic labels and sex chromosomes is also common.

As is the case for all stigmatised minority populations, language choices vary from person to person, and depending on where used. It is particularly notable that only 3% of respondents use the clinical term “disorders of sex development” to describe themselves, while 21% use that term when accessing medical services. From our perspective, this shows a perceived necessity or obligation to use pathologising language in order to receive adequate medical treatment.

Medical treatment

“[Gonadectomy]…exists in my memory as some type of clinical rape; 10 student doctors standing around staring up my vagina as the doctor put his fingers in me and spoke about me like I wasn’t there. Everyone was complicit in this, my parents, extended family, the doctors, the state as far as I knew, the whole world.”

(statement by respondent)

- 60% reported having had medical treatment interventions related to their intersex variation.

- Over half of the reported treatments occurred when the participants were under 18yrs, most commonly genital surgeries (many of which occurred in infancy) and hormone treatments.

- Most participants were given no information on the option of declining or deferring treatments; a fifth were given no information at all about any of treatments they received.

- The majority of participants listed at least one negative impact from their treatments, for some these were life-threatening.

The report states:

Of the 117 responses, a strong majority of 97 responses described one or more negative impacts (including 74 responses which described only negative impacts from interventions).

[Overall] there was strong evidence suggesting a pattern of institutionalised shaming and coercive treatment of people with intersex variations

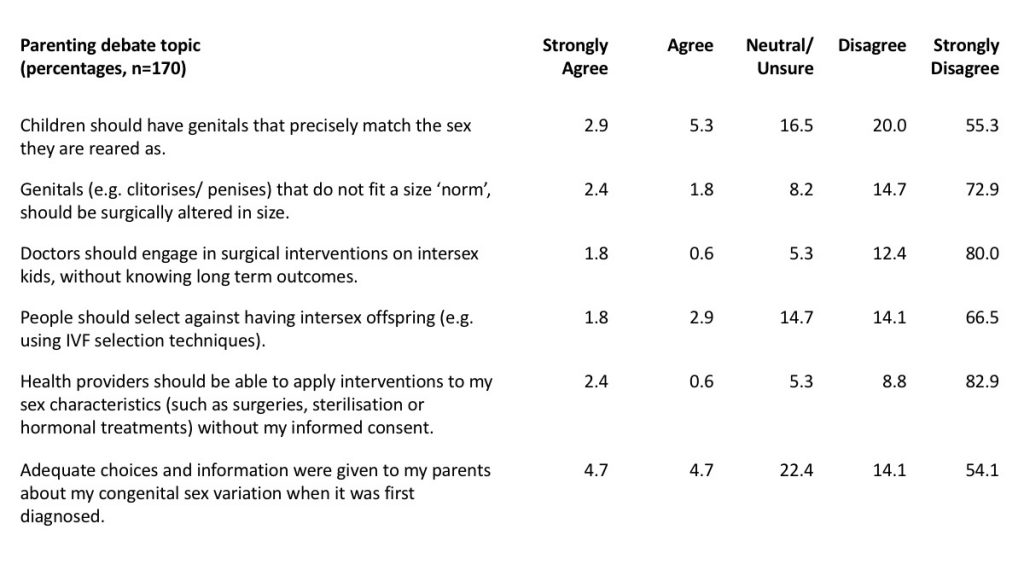

Respondents broadly rejected standard medical practices on children with intersex variations.

Responses to questions about medical practices, particularly those of early childhood.

Mental health

A majority of participants rated their current mental health as good or better. Nevertheless, “60% of the participants had thought about suicide, and 19% had attempted it, on the basis of issues related to having a congenital sex variation.” This compares to less than 3% of Australians who consider or attempt suicide.

44% of the group reported receiving counselling/training/pressure from institutional practitioners (doctors, psychologists etc.) on gendered behaviour; 43% reported it from parents.

The data appear to show resilience amongst survey participants.

Education

Experiences of education are, in many cases, significantly impacted by sex characteristics, including through bullying and medical treatment coincident with puberty:

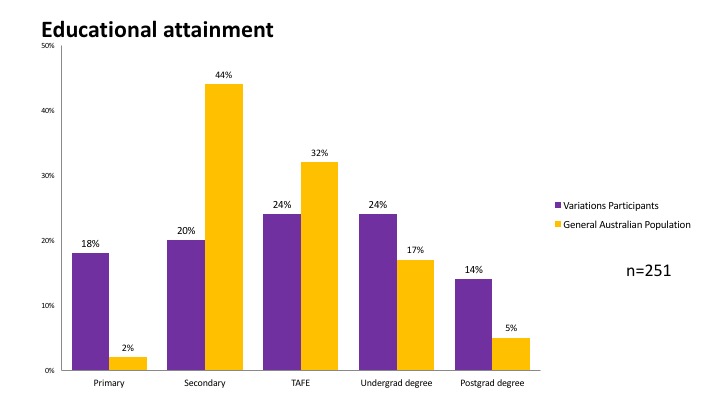

Most (62%) people with intersex variations had a post-secondary qualification, however a much higher portion (18%) had not completed secondary school compared to the general Australian population.

Educational attainment

2% of Australians fail to complete secondary school. Most students left school around the eighth-ninth grade, during years most associated with pubertal development, but also with hormone and surgical treatments and examinations.

“I nearly died of septicaemia as a teenager, due to my genital surgery, I missed so much school I actually had to drop out entirely. It changed my whole life. Immense emotional impact to this day.”

(statement by respondent)

“My school principal, teacher and counsellor made it hard for me to get the time off school I needed and did not understand the need to deal with the situation in the time it took. My classmates either thought I was a freak or did not understand what was going on and saw me as a bludger trying to get out of class (I was bleeding like a stream from my vagina for god’s sake, it is not something you want to say is happening or go to school with).”

(statement by respondent)

Education was not inclusive of information about intersex traits, and many people experienced bullying. Some intersex traits may sometimes be accompanied by development delays, however, this should not impact on school attendance and completion.

At the same time, a higher rate of people born with atypical sex characteristics have graduate and postgraduate qualifications.

Employment

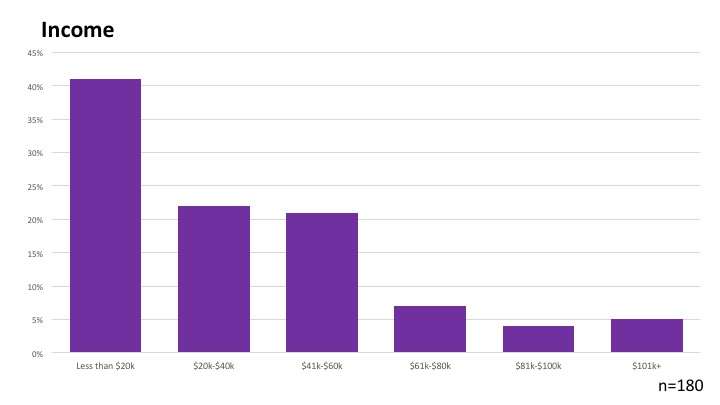

Income levels

41% of respondents were in the lowest income bracket, earning less than $20,000 per year, and 63% earn under $41,000 per year. For comparison purposes, the ABS report that the median full time income at the time of the survey was $80,000 and the figure for “All employees average income” was just under 60,000 ($59,576).

The report shows high rates of poverty, perhaps impacted by high rates of early school leaving and higher rates of disability.

Social support and discrimination

Peer support and advocacy groups play a key role.

“Meeting happy, healthy intersex people online caused a complete and radical shift in my thinking and wellbeing. Seeing that they had come out about being intersex, and that they liked themselves, that some had partners, and that they sometimes even talked about having had and enjoyed various kinds of sex, that they had found all these ways to have children and jobs and lives… BEST. THING. EVER!”

(statement by respondent)

The research also shows the importance of discrimination protections introduced federally in 2013:

- 66% of participants had experienced discrimination on the basis of their intersex variation from strangers.

- Most (70%) never or rarely discussed their variations with strangers, and could risk being exposed to common myths about their identities in discussing the topic. Conversely, most (65%) said engaging with others with their variation or similar improved their wellbeing.

“Apparently nothing is visible of my condition. The biggest problem is not the disclosure of the symptom but the ignorance of people who do not know the differences that unite us”

(statement by respondent)

“…derogatory stuff about hermaphrodites or people who did not fit sex norms, about women who choose not to have or cannot have babies, about people who don’t have ‘real female bodies’… these rules on who can be what impact me so much. Most of all, I hate it when people make rules about what intersex people should do with their bodies.”

(statement by respondent)

“laughed at and insulted with his shirt off, like at the pool or beach”

(statement by respondent)

Conclusions

“Research is fine but we need legislation to protect unconsenting infants from indiscriminate knives. Certainly more research in the area of effective HRT, the long term effects and better delivery systems, I am taking the pill for my hormone needs and have no wish to be on it for the rest of my life. Also a long term health plan for intersex individuals as to risks to disease etc. I truly believe that being intersex is amazing and it is completely normal in the sweeping expanse of the human narrative, but I think it is time to take the pen from whoever has been writing the story.”

(statement by respondent)

Tiffany Jones et al state:

Intersex status appeared not to be something people feel intrinsically bad about in itself, as in the historic psychological and medical theorisation supporting early intervention (Jones and Lasser, 2015); instead, most participants found their exposures to social and medical constructions of their intersex status played important roles in how they felt about their intersex variations. There were very clear cut issues around medical intervention, the lack of structural support features in schools and impacts on employment for some. People with intersex variations also seemed to have mainly uniform positions on a few matters currently being debated around their inclusion in society (such as on surgical intervention and other themes). Most did not widely discuss their variation with other people in their own lives, yet most benefitted from reaching outside their social circles to engage in social interactions of some kind (whether in groups, online or otherwise) with people with their own intersex variations or similar…

Most participants in this study had experienced around two treatment interventions, most commonly hormonal treatments and genital surgeries of varying kinds, and many of the key issues around these treatments arose around the fact that over half were delivered when they were aged under 18yrs – at a time when, and in ways where, their right to be able to make fully informed decisions about treatments were often overlooked. With the majority of participants receiving no information about risks related to the interventions and one fifth receiving no information at all, people with intersex variations were often uninformed about their rights as patients and in some cases class themselves as being coerced or outright abused by individuals and processes in medical institutions. This has created, for a noteworthy portion of this population, feelings of anger and trauma around medical services, and in some cases people now actively avoided them – which is worrying in light of the fact that people with intersex variations, like anyone else, may have physical health needs or illnesses for which medical help can be useful…

Finally, it is undeniable that a few individuals in this study had suffered a unique and extreme form of trauma from the multifarious impacts of being subjected to unnecessary and damaging medical interventions without their consent.

Thank you again to survey participants, Tiffany Jones and University of New England, to co-authors and the publisher.

More information

The following papers outline many of the statistics on this page:

Jones T. The needs of students with intersex variations. Sex Education. 2016 Mar 11;16(6):602–18. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14681811.2016.1149808

Jones T. Intersex and Families: Supporting Family Members With Intersex Variations. Journal of Family Strengths. 2017 Sep 7;17(2). Available from: http://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol17/iss2/8

The full work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Tiffany Jones, Bonnie Hart, Morgan Carpenter, Gavi Ansara, William Leonard, and Jayne Lucke, Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0089

The report is currently unavailable, but we hope it will become available again very soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.