Karin: Lili Elbe’s autobiography, Man into Woman

Download a copy of this book review as a PDF

Published autobiographies written by intersex people are rare. Socially-imposed guilt and shame at being born intersex have led to fewer such books being published than one might wish for – we can learn so much from how others like us have lived.

I’d always known Lili Elbe as being one of the few earliest publicly known intersex people, after Herculine Barbin, but beyond the salient facts that she had been an artist, as I am, and died just before the Nazis came to power, I knew little more. Sexology commentators mentioned her only briefly and with skepticism, and others laid claim to her being one of their own. The fact of Lili being intersex as well as the first person to medically transition was erased, replaced solely with something else created for other people’s ends and not our own.

Lili on Film

Then, when it was announced that Nicole Kidman was to coproduce and star in a movie based on Lili’s life, and the media sensationally misportrayed Lili as “the world’s first post-operative transsexual,” I decided to see if I could dig up some facts.

I arrived at Man into Woman via David Ebershoff’s bestselling fictionalisation of Lili’s story, The Danish Girl, upon which the film is based. Ebershoff mentions that he went to Europe to seek out newspaper reports of Lili’s surgeries and subsequent life, and then I remembered some previous scanty reports of a book apparently written by a friend of hers back in the 1930s.

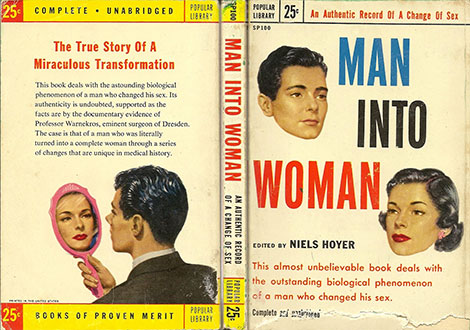

Although it had been first issued then, and published again in the 1950s as a sensationalist pulp paperback, a British publisher had released a new translation several years ago. The book turned out to be Man into Woman, and it is still available from the publisher, Blue Boat Books, as well as Amazon.co.uk.

The Real Author

Lili herself is the actual author of the book. The friend, sometimes mistakenly described as the author, was actually her editor, and assembled the manuscripts for publication after Lili’s death. His pseudonym was Niels Hoyer, and his real name was Ernst Ludwig Hathorn Jacobson. Lili gave pseudonyms to other friends she mentions in her book, in order to protect them from the public exposure she could not avoid for herself.

Einar Wegener, 1929.

Lili also uses a variation of her wife’s actual name when writing about her. Gerda Gottlieb Wegener becomes Grete in the book, while Lili substitutes Andreas Sparre for her birth name of Einar Mogens Wegener.

Einar Wegener was born in rural Denmark in 1882. Gerda Gottlieb was born in Copenhagen on 15th March (my own birthday, and the Ides of March), in 1885 or 1886. They met at the Copenhagen Art School, and married in 1904, when Einar was 22 and Gerda was 18 or 19.

Both were painters – Einar painted landscapes, having won prizes for his work, and Gerda specialised in portraits and was also an illustrator. After travelling through Italy and France, the couple settled in Paris in 1912.

Lili’s Wife

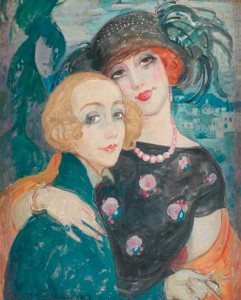

Gerda became famous for her paintings of fashionably-dressed and beautiful sloe-eyed women, as well as her erotic illustrations for books by Casanova and contemporary authors.

Einar, though considered the more talented, came to put Gerda’s career above his own, to the point of eventually becoming his wife’s favourite model, as a woman. It seems that he was often taken for a young woman dressed in men’s clothes as he went about his business in the city of Paris.

Gerda and Lili, painted by Gerda Wegener.

Gerda, for her part, was reputed to be sexually attracted to women. Some of her most renowned illustrations seem to bear that possibility out – they feature female couples in sexual congress. Her portraits, commissioned and otherwise, are credited with contributing to the iconic ideal woman of her time, along with Polish-born painter Tamara de Lempicka’s own more hard-edged Art Deco depictions of women.

Lili Wakes

Lili credits one of Gerda’s early portrait commissions with awakening her awareness of herself within the persona of Einar Wegener:

“About this time Grete painted the portrait of the then popular actress in Copenhagen, Anna Larsen. One day Anna was unable to attend the appointed sitting. On the telephone she asked Grete, who was somewhat vexed: ‘Cannot Andreas pose as a model for the lower part of the picture? His legs and feet are as pretty as mine.’”

Andreas, or rather Einar, did so with great reluctance, and when Anna Larsen unexpectedly arrived at the studio during the sitting, to see Einar dressed up and posing instead of her, she nicknamed her stand-in Lili.

“You know, Andreas, you were certainly a girl in a former existence, or else Nature has made a mistake with you this time,” the actress reportedly said.

Lili began to pose regularly for Gerda. Gerda and Einar later moved to Paris after suspicions arose about who her mysterious female sitter really was, scandal hot on their heels, along with the threat of exposure by a Danish quack radium doctor Einar had consulted for a cure.

Paris is a far larger, more cosmopolitan city than Copenhagen. More opportunities for Lili to show her face in public existed in the French capital than Denmark. Anonymity was so much easier to maintain when she did so.

And go out she did, to the artists’ balls and public events common in the pre-war and between-wars periods. Lili started to appear at home too, and in Gerda’s studio, at her behest, and the paintings and sketches that made her famous began.

“Grete’s artistic fame spread. But nobody knew who was concealed behind the model. Legends sprang up around it…. One day Grete received an invitation from Paris to exhibit her ‘Lili sketches.’ And so the three of us were transplanted to Paris: Grete, I, and – Lili.”

Lili’s Life and Her Book

Lili wrote what became Man into Woman through the period of her surgeries in the early 1930s, as a form of therapy and to help explain herself to the world at large. A Danish edition came first, followed by one in German, then the English translation that was published in 1933.

Lili Elbe, Copenhagen, October 1930.

In the style of the time, the translation’s name was long – Man into Woman: An Authentic Record of a Change of Sex: The true story of the miraculous transformation of the Danish painter Einar Wegener (Andreas Sparre).

Miraculous might not be the right word – foolhardy is more like it, or perhaps determined. Lili had set her heart on a series of risky, essentially unproven operations to remove her male parts and transplant female reproductive organs into her body so that she could become a mother.

These were the early days of transplant surgery – the immune system was little understood and while organ rejection was a known possibility, its mechanism was not known in depth. Lili knew the operations carried great risk, and might prove fatal, but she had endured life as Einar for far too long. She was nearing 50 when she died.

We don’t know what intersex variation Lili actually had. Speculation is pointless – even though some biological variations that can underly intersex have been named since the Second World War, few if any such names and definitions existed in Lili’s time.

Lili herself is a somewhat unreliable witness whose concerns were more about her imminent new life than its causes – understandable given the enormous challenges ahead of her. She relates being told by her surgeons that she had testes and underdeveloped ovaries, though. It was that information that saw Lili dismissed as not really being intersex by some writers.

Generally speaking, most people only have one set of reproductive organs even if different elements of it are male and female. But exceptions have been known to occur – mothers with two reproductive systems are reported in the media every so often.

I have come across reports of intersex people with two sets of reproductive organs, one male and one female, both underdeveloped, in one instance made by a scientist who knows the person well. In that case, the intersex person had self-fertilized and the fetus was stillborn, never having left its parent’s body.

We are still in the early days of research into intersex and its underlying causes. The belief that intersex is incredibly rare is common. Yet experts like Milton Diamond put its prevalence at 1 in 100 while Australian genetics researcher Peter Koopman puts it at 4%. Perhaps Lili did have both ovaries and testes – we will never know for sure, and it does not really matter here.

Chimerism, a variation that can sometimes result in having two reproductive systems, is traditionally believed to be one of the more rare intersex differences. Perhaps, but some scientists believe that many potential twin, or triplet, births result in two siblings being absorbed into one, with the resulting child’s body containing two different lines of DNA.

I came across this paragraph in The New England Journal of Medicine:

“High rates of successful pregnancy after in vitro fertilization depend on placing more than one embryo into the mother, a practice resulting in a 30-to-35-fold increase in dizygotic-twin deliveries. Increased frequencies of twin-associated anomalies might also therefore be expected. Chimerism, the presence in a single person of cells derived from two or more zygotes, is one such rare anomaly. It is usually ascertained through anomalous blood-grouping results or (for XX/XY chimeras) sex reversal or intersex.”

I am personally motivated to read these kinds of articles – my partner is a chimera, a twin, born with anomalous and extra body parts, and she may have originally been one of triplets. Like others we know, she has co-morbidities that can make life challenging.

Spending Time With Lili

We read the life stories of intersex people all too rarely. Many of us have suffered badly for being intersex, especially if we have rejected the sex we were assigned at birth, and our tales can make for disheartening reading. But even so, it is an honour and a privilege to read all such stories, happy or sad, because telling our own stories can extract a price. I value the stories of all intersex people as a precious gift.

I am grateful to Lili for having shared her history with the world. To some degree, she had little choice. When she went back to Copenhagen in between operations, she was outed by an associate to the Danish press, and if the truth was to be told, to take the place of speculation and scandal, then best she tell it herself.

That must have demanded enormous courage of Lili. Einar had been a well-known painter. Copenhagen was a small city. Lili and Gerda’s friends, relatives and former schoolmates still lived there. The couple staged an exhibition to raise money towards the cost of Lili’s surgeries. When Lili’s story hit the newspapers, her paintings failed to sell. They only began to find buyers after Lili’s early writings about herself appeared and people understood she was not the pitiful freak they feared after all.

Lili relates a key incident. She visited the gallery each day, watching the crowds eager to catch a glimpse of the strange creature they had read about. Nobody recognised her. One day an old woman approached:

“Tell me, miss, don’t you think that the lady over there with the large feet and the necktie, who looks like a man, is Lili Elbe?”

“Yes,” answered Lili, “most decidedly that is she.”

Lili, Copenhagen, 1931.

Some days, Lili would stroll about the city, unremarked upon by other women, while men made approving comments on her attractiveness amongst themselves. Once, the men included her former art school colleagues. Yet, to her distress, none of Einar’s male friends ever visited her – a not uncommon occurrence when people reject their birth assignment to simply be themselves.

Lili’s Puberty & Future

We don’t know whether Einar experienced a complete first puberty, a partial one, or none at all. Nonetheless, Lili woke up after the removal of her testes in what comes across as a fully-fledged female puberty.

Puberty late in life is a daunting prospect. Puberty at the usual age for it is hard enough. Late puberty for someone who was assigned the sex they actually are not, then undergoes urogenital surgery and HRT, is incredibly difficult. I should know.

For the first time in your life, you are the person you should have been, or as close to it as you ever been before. When you wake up after being on the operating table, you are waking up as you for the very first time. If, like Lili, you are going through a series of operations then you are doing it again and again, by degrees.

No wonder she seems a little lost, bewildered, apprehensive, throughout her surgeries. She has placed herself in the hands of her surgeon, Kurt Warnekros of the Dresden Municipal Women’s Clinic – Dr Werner Kreuz in the book – as if he is her guardian and protector, the creator of her life and her future.

Lili has no idea how she is going to live when the surgeries are completed. She has lost the artistic impulse that carried Einar through his forty plus decades. She does not know whether she will get it back, whether her talents will equal his, and what her reception from the art world may be if she does ever paint again.

I discovered that my own creative work radically improved, and changed in nature, after urogenital surgery. For several years though, I did not even want to look at a camera or a keyboard. I have no idea how the art world will regard my work, or me, from this point onwards.

I was never established as an artist like Einar was. My most well known project from before has never been exhibited in its entirety, only in subsets. The first joint exhibition containing 12 images from it, out of 108 in total, is about to be staged in the city I have lived in the longest, and where the project was created. It will be shown under my current name, not my previous one.

I would rather show new work, and establish a whole new career in my new name as if my former life never existed, but I cannot deny the power and the importance of that first still mostly unrevealed project, and the necessity to give it a complete public showing one day.

[Editor: The project described as about to be shown, above, has now been written about by an art museum curator as ‘the most significant photo-series’ on its subject. The author’s new work is now receiving a great deal of praise.]

All artists rely on provenance and progress to build their careers, a succession of shows, press clippings, and sales. Being a tabula rasa as an artist for the second time is as hard as starting out fresh after art school, and as uncertain. The fact that one may have a past some find scandalous, others unacceptable, makes it even harder. I felt for Lili, and knew her pain, as I read her thoughts on the same subject.

A Second Australian Connection

There is another Australian connection in the story of Lili Elbe, besides Nicole Kidman’s involvement in the film adaptation. Norman Haire wrote the introduction to the 1933 edition of Man into Woman, signing off at his Harley Street, London medical practice address.

Haire was one of the leading sexologists of his day, perhaps the most famous next to Havelock Ellis, whose early work had persuaded Haire to pursue sex as a subject and who had, coincidentally, been a student teacher at Haire’s own school in Sydney – Fort Street Model School on Observatory Hill, The Rocks, now Fort Street High School in Petersham.

Ellis introduced Haire to Magnus Hirschfeld, the sexologist whom Lili Elbe consulted in Berlin before her first surgery, and who arranged it for her through his Institut für Sexualwissenschaft. Haire described Germany as his spiritual home. The University of Sydney’s Faculty of Medicine, as a result of Haire leaving his estate to the institution, awards the Norman Haire Fellowship every so often.

Haire’s introduction speaks of Lili being intersex, in the terms of the day, and concludes that, given her surgeries’ tragic outcome, Lili may well have been better off seeking “psychological treatment.”

“I cannot help thinking that until we know more about sexual physiology it is unwise to carry out, even at the patient’s own request, such operations as were performed in this case,” Haire concludes.

Perhaps, if psychology could actually substitute for human physiology, but given the events in Europe that occurred not long after Lili’s last surgery – the rise of Nazism, and the Second World War – her life may have been forfeit had she lived a little longer anyway.

External Links:

Man into Woman, front cover, 2004 edition.

You must be logged in to post a comment.