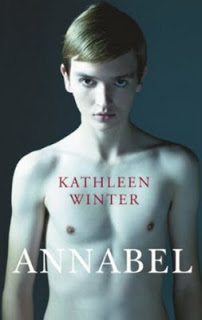

Kathleen Winter’s book, “Annabel”

Kathleen Winter’s book Annabel is based on a short story originally intended for her collection boYs but rejected because it was too fantastic. Unfortunately, the same can be said of the novel itself. While literary and entertaining for its descriptions of Newfoundland, the lead character shows what happens when a preoccupation with gender dominates at the expense of an understanding of biology.

Tall and debonair, with a striking resemblance to her beloved kid brother, Winter explains her unusual inspiration as if it was the most natural thing in the world. “I’ve always been interested in gender, and I was really interested in what would happen if you found that out about yourself in such a tiny place,” she says. …

The estimable John Metcalfe edited Winter’s debut collection of short fiction, titled boYs and published in 2007 to multiple awards. But he reacted badly to her story about a person with two sets of genitals being raised as the son of a hard-bitten trapper down the coast past Happy Valley. “He said it was way too unbelievable,” Winter reports. …

To be absolutely clear about a fundamental flaw in the book: there have been no recorded instances of self-impregnation by any human anywhere. The biological circumstances depicted in the book are fanciful, and essentially appear based on misconceptions of intersex as hermaphroditism. Very many people with intersex variations regard the term hermaphrodite as pejorative or, at the very least, misleading because humans, indeed all mammals, are not able to reproduce alone.

A form of biological determinism is evident in the book’s treatment of Wayne/Annabel, insofar that discovery of a fictitious intersex trait appears, ipso facto to require a non-binary gender identity, or dictate gender identity confusion. This is reductive: identity and biology are not necessarily intertwined in this way. In reality, many people with intersex differences do have gender identities that are informed by their intersex variation, but our identities are hugely diverse. And many intersex people have a typical gender identity as a man or woman.

Moreover, fears around perceptions that intersex traits subject an individual to gender identity confusion form rationales for medical interventions aimed at “normalising” the bodies of infants and children.

In a world with so few positive, realistic portrayals of intersex, we had looked forward to reading this book but, sadly, we are unable to recommend it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.