Marriage and people with intersex variations

This paper discusses the role of medical interventions in preparing intersex bodies for marriage, as well as issues with access to marriage. It provides an update on the implications of marriage laws in Australia.

9 January 2017

Submission on the Exposure Draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill

1. OII Australia

Organisation Intersex International Australia Limited (“OII Australia”) is a national, intersex-led organisation for people born with intersex variations. It promotes the human rights and bodily autonomy of intersex people in Australia, and provides information, education and peer support. OII Australia is a not-for-profit company, with Public Benevolent Institution (charitable) status. In late 2016, we secured philanthropic funding sufficient to employ staff for the first time; since December 2016, we have two part-time executive directors. This funding does not support this submission on the Exposure Draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill.

2. Intersex

OII Australia refers to intersex in this document in line with a definition of intersex by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights:

Intersex people are born with physical or biological sex characteristics (such as sexual anatomy, reproductive organs, hormonal patterns and/or chromosomal patterns) that do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies. For some intersex people these traits are apparent at birth, while for others they emerge later in life, often at puberty.[1a]

We use this term to include all people born with characteristics that do not fit medical or social norms for male or female bodies. In doing so, we acknowledge the diversity of intersex people in terms of our legal sexes assigned at birth, our gender identities, and the words we use to describe our bodies.

Many forms of intersex exist; it is a spectrum or umbrella term, rather than a single category. At least 30 or 40 different variations are known to science;[2] most are genetically determined. Since 2006, clinicians frequently use a pathologising and stigmatising label, “Disorders of Sex Development” or “DSD”, to refer to intersex variations. This is rarely used, by choice, by people born with atypical sex characteristics.[3]

Intersex variations can include differences in the number of sex chromosomes, different tissue responses to sex hormones, or a different hormone balance. Examples of intersex variations include androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), and sex chromosome differences such as 47,XXY (often diagnosed as Klinefelter syndrome) and 45,X0 (often diagnosed as Turner syndrome).

3. Marriageability and harmful practices

The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights states:

Because their bodies are seen as different, intersex children and adults are often stigmatized and subjected to multiple human rights violations, including violations of their rights to health and physical integrity, to be free from torture and ill-treatment, and to equality and non- discrimination.[4]

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, Committee Against Torture, Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and other human rights and child rights experts details some aspects of this:

In countries around the world, intersex infants, children and adolescents are subjected to medically unnecessary surgeries, hormonal treatments and other procedures in an attempt to forcibly change their appearance to be in line with societal expectations about female and male bodies.[1b]

Rationales for such interventions in Australia include marriage prospects, aimed at minimising “psychosocial risks”, including in a 2010 ethical framework developed in Victoria,[5] and widely adopted nationally.[6] In 2013, the Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee cited a derivative 2013 Victorian government decision-making framework on the treatment of intersex infants, children and adolescents:

- risk of social or cultural disadvantage to the child, for example, reduced opportunities for marriage or intimate relationships[7a]

The word “marriage” was recently, and quietly, removed from the State decision-making framework, as if it had never been mentioned.[8] Nevertheless, there is no evidence that clinical practice has changed, either through publication of the 2010 ethical guidelines[9a] or following the quiet removal of the word “marriage” from the derivative State version.

Surgical interventions to address such “psychosocial risks” persist in Australia, evidenced for example in the 2016 Family Court of Australia case, Re Carla, reported widely in December 2016, including by The Australian[10] and SBS.[11] The case disclosed the medical history of a 5-year old child with an intersex variation including what the judge disturbingly described as surgery that “enhanced the appearance of her female genitalia”[judgement paragraph 2].[12] These surgeries were a clitorectomy (“‘clitoral’ recession”) and labioplasty,[paragraph 16] and they took place entirely without Court supervision. The judge permitted parents to authorise the child’s sterilisation (subsequent to the clitorectomy and labioplasty), noting that she would subsequently require a lifetime of hormone replacement therapy. Similarly, the Family Court judge stated that the 5-year old would require further surgeries to prepare her body for heterosexual intercourse: “Carla may also require other surgery in the future to enable her vaginal cavity to have adequate capacity for sexual intercourse.”[paragraph 18]

There is, however, no clinical consensus regarding indications, timing, procedure or evaluation of surgical interventions to “normalise” intersex bodies.[13a] Nor is there systemic evidence for what a major clinical paper states as a “belief” that surgical interventions in early childhood tackle purported psychosocial risks.[14] Further, such interventions on intersex children are unregulated in this country, lacking systemic disclosure, and lacking independent oversight. As indicated in Re Carla, interventions such as clitorectomies and labiaplasties in young children do not require Court consent; the Court has been unable to provide independence on matters put before it. A specific exemption exists in policy frameworks prohibiting female genital mutilation.[15] Nevertheless, the impacts are profound and lifelong, including an impact on capacity for intimacy and sexual functioning. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, Committee Against Torture and Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities state:

Profound negative impacts of these often irreversible procedures have been reported, including permanent infertility, incontinence, loss of sexual sensation, causing life-long pain and severe psychological suffering, including depression and shame linked to attempts to hide and erase intersex traits.[1c]

For both physical and psychological reasons, the consequences of early and unwanted medical “normalisation” are lifelong, and can adversely impact capacity for intimacy and lifelong relationships.

Pressure to be marriageable is also psychological in nature. A recent independent Australian study on 272 people born with atypical sex characteristics revealed “strong evidence suggesting a pattern of institutionalised shaming and coercive treatment”.[16a]

Of the survey respondents, 44% reported receiving counselling, training or pressure from institutional practitioners such as doctors or psychologists on gendered behaviour; 43% of respondents reported this from parents. It included pressure to act or dress more in line with gender stereotypes, and pressure to become capable of penetrative sexual intercourse with a partner in the context of a heterosexual marriage.

The marriageability of people with intersex variations thus remains of central importance to clinical teams that conduct surgical and hormonal interventions on the bodies of infants, children and adolescents with intersex traits.

4. Third sex classifications

Intersex is sometimes othered, or framed as a third sex. For example, the 1979 Family Court case In the marriage of C and D (falsely called C) saw the annulment of a marriage of a man with an intersex variation. The husband was born and raised male, but had chromosomes typically associated with females.[17a] His wife sought an annulment based on non-consummation of the marriage, although we note that the Family Court will not declare a marriage invalid on the ground on non-consummation.[18] The marriage was annulled on the basis that:

Marriage as understood in Christendom is the voluntary union of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others for life, and since the respondent was a combination of both, a marriage in the true sense could not have taken place and did not exist[17b]

There are disturbing ironies in such a decision, given the use of marriageability as a rationale for medical interventions in childhood, designed to prepare intersex bodies for heterosexual intercourse, but this is illustrative of the contradictory and disjointed policy environment facing people born with intersex variations in Australia.

In 2014, the Australian Capital Territory created third and other sex classifications in reforms to birth registrations.[19] This also has direct implications for marriage as individuals so classified are unable to marry in Australia.

The classifications are available to any individual, regardless of age. Indeed, in communications with our president at the time, the Hon. Katy Gallagher, then the ACT Chief and Health Minister, wrote that the creation of a new sex category would address issues around coercive medical interventions on infants and children. In doing so, the Minister neglected to consider the responsibility of her government, and other Australian governments, for such medical interventions. In April 2014 she wrote:

The availability of the third marker for children will also reduce the risk that parents will force their child to conform to a particular gender or subject them to gender assignment surgery or other medical procedure to match the child’s physical characteristics to the chosen sex[20]

OII Australia would not encourage children to be so classified. The latest information we have (unfortunately our information is dated, from August 2015)[21] is that no children have been so classified, and we believe that the legislation has no impact on the stated medical procedures. OII Australia opposed the legislation on the basis that creating a third sex classification for infants and children would in fact promote such interventions on the basis that vulnerable parents will fear repeated public disclosure, and instead seek greater certainty, as well as follow actual clinical advice. The clinical framing of intersex as a disorder of sex development is evident in a contradictory but contemporaneous letter from the same Minister, a couple of months prior:

Currently in the ACT, in the event of a birth of a baby with a disorder of sex development (DSD), clinicians follow a standard investigation and management practice that is consistent with a national approach from the Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group and international consensus statements from key disciplines such as paediatric endocrinology, surgery… it is recognised that surgery of this sort is best performed in centres of excellence. For this reason children with a DSD are normally referred to either Melbourne or Sydney.[22]

The national approach towards management practices and surgeries is evidenced in the clitorectomy and labiaplasty “enhancements” described in the Family Court case Re Carla. Additionally, the concept of consensus is flawed: the Senate found in 2013 that “there is no medical consensus around the conduct of normalising surgery” in Australia.[7b] Indeed, in 2016 a worldwide clinical statement said:

There is still no consensual attitude regarding indications, timing, procedure and evaluation of outcome of DSD surgery. The levels of evidence of responses given by the experts are low … Timing, choice of the individual and irreversibility of surgical procedures are sources of concerns. There is no evidence regarding the impact of surgically treated or non-treated DSDs during childhood for the individual, the parents, society or the risk of stigmatization[13b]

The creation of a third sex classification for children is as flawed as medical interventions designed to minimise risks to marriageability and “enhance” female genitalia in a young child. Both are equally based on adult perceptions of who a child should be, and how they should be classified by society, rather than who the child and future adult is, and what they want for themselves.

OII Australia also opposed the legislation in ACT on the basis that the ACT government had no coherent understanding of the population affected. The simultaneous existence of two contradictory and disjointed policy frameworks in ACT and elsewhere in Australia demonstrates a continued lack of understanding of the reality of intersex lives and human rights issues, and perpetuate harmful practices on intersex bodies.[9b]

These are matters of grave and ongoing concern to OII Australia. Parliaments and governments need to properly engage with intersex-led organisations to resolve these issues.

Nevertheless, intersex adults have many ways of understanding sex, including intersex adults who understand themselves as both male and female, neither, or non-binary. OII Australia supports opt-in classifications by adults. In this, we support the demands of the 2013 Malta Statement.[23]

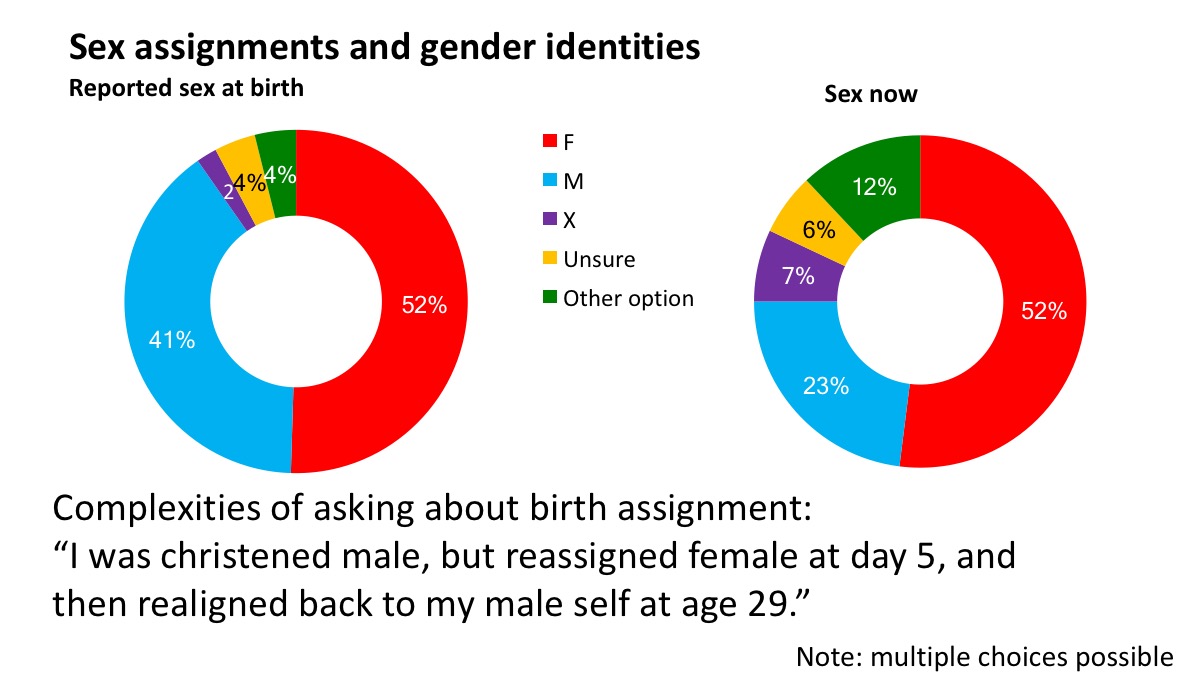

Independent Australian sociological research on 272 people born with atypical sex characteristics,[16b] showed the following reported sex at birth, and sex at the time of the study:

Initially, 52% of respondents were legally assigned female, 41% were assigned male, and 10% of respondents selected other options. The “Sex now” data show status at the time of the survey: 52% of respondents indicated that they were female, 23% indicated that they were male, and 25% selected a variety of other options. 19% chose X or an other option. Multiple choices were possible.

These data show that one single legal sex classification is not appropriate for all intersex people. Nor, for that matter, are persons who identify as members of a third sex or third gender necessarily intersex.

These data also show that people born with atypical sex characteristics are more likely to reject the sex of rearing or be gender fluid than the general population. One quarter of respondents had sex markers or gender identities other than female or male; conversely, 75% are female or male. These classifications or identifications deserve respect.

Any persons classified other than man or woman (whether classified by themselves or by others) should not be exposed to discrimination, nor exclusion from any public institution, including the institution of civil marriage.

5. Marital statuses

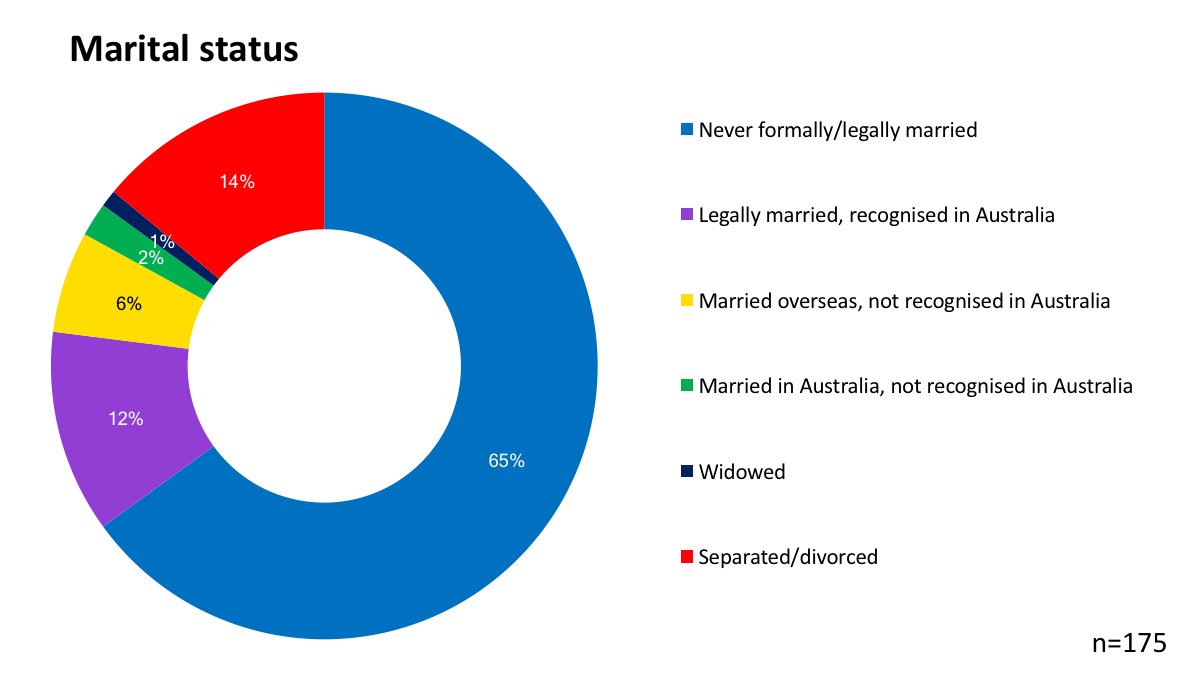

In the independent Australian research on people born with atypical sex characteristics, 12% of respondents are legally married, recognised as married in Australia. At the same time, 8% of respondents are married, either within Australia or overseas, but their marriages are not legally recognised here.

This diversity of marital statuses in part reflects a diversity of sex and gender markers, including legal assignments at birth, and a diversity of sexual orientations.

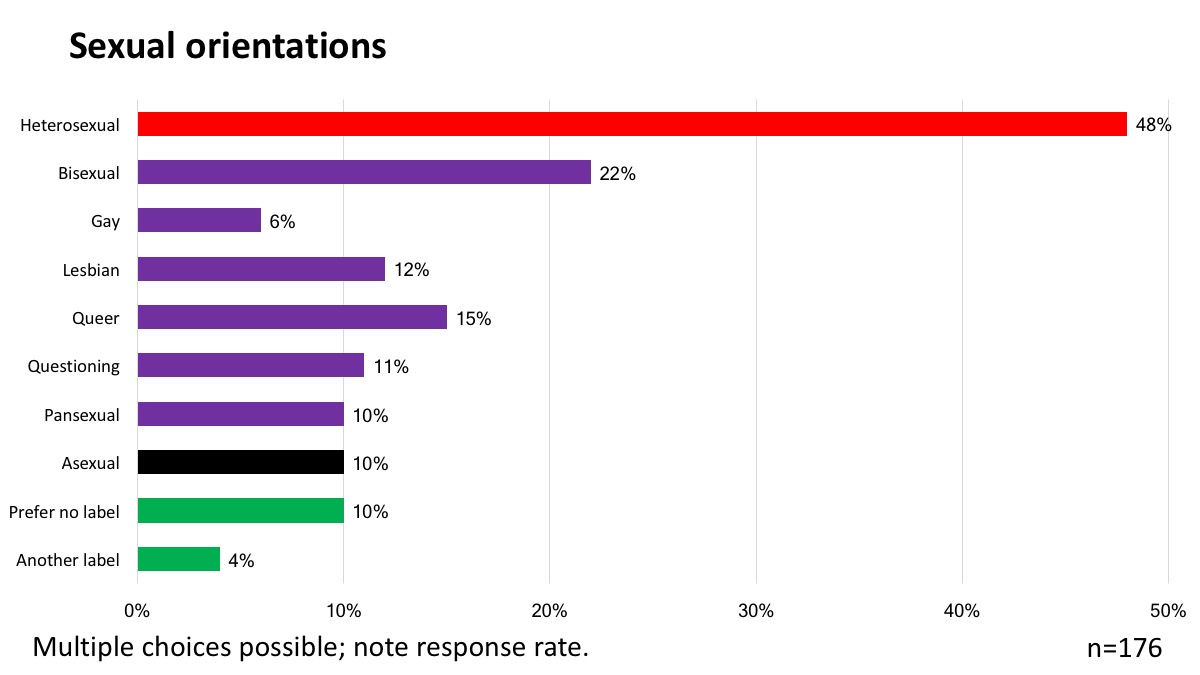

In the study, 48% of respondents stated that they were heterosexual, while 22% selected bisexual, 15% queer. An unusually large percentage (10%) of people described themselves as asexual, and this may reflect consequences of medical interventions on capacity for intimacy. The same percentage “prefer no label” and 4% prefer “another label”. Multiple choices were possible.

The data shows that people born with atypical sex characteristics are more likely to be non-heterosexual than the general population. There is also a need to recognise that many intersex people are heterosexual; this means that many “LGBTI” people are heterosexual.

This Australian sociological research is supported by clinical research that also show higher rates of same-sex attraction and changes in sex assignment amongst intersex people than amongst the general population; such research typically problematises sexual orientation and gender identity.[24]

Despite the ease with which heterosexual intersex women and men can access marriage, many carry fears about the status of their marriage, While the ruling in Re Kevin,[25] a Family Court case recognising the marriage of a transgender man, would seem to also extend by analogy to the marriages of intersex men and intersex women, the case of In the marriage of C and D casts a shadow of doubt over many marriages of intersex people.

In several States and Territories, current legislation requires that individuals changing legally-recognised sex assignment be unmarried. For example, section 32B of the Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1995 in New South Wales requires that applicants to register a change of legally recognised sex must be made by a person “who is not married”.[26] This legislation arises from the federal recognition only of a man and a woman, and it unnecessarily and adversely impacts upon some intersex people.

6. Recommendations on Exposure Draft

OII Australia warmly welcomes publication of the Exposure Draft, and we commend this Senate inquiry for considering issues raised by the Exposure Draft.

Current policies and practices in Australia problematise the future marriageability and capacity for heterosexual intercourse of infants, children and adolescents with intersex variations. This promotes harmful and unnecessary interventions to “enhance” genitalia without independent oversight. At the same time, current policies and practices promote the use of third sex classifications that, ipso facto, exclude persons so classified from the institution of marriage. Further, a Family Court judgement promotes a shadow of doubt as to the legality of marriages involving heterosexual, non-transgender, intersex men and women. Current legislation also excludes intersex people who have other understandings of themselves and their relationships from participating in marriage.

Current policy and practices are, therefore, deeply contradictory and a source of great harm.

Equalising access to marriage is only one small step in resolving those contradictions, but we welcome the equalisation of access to marriage for all intersex and non-intersex people in Australia. If passed, this Bill may bring joy to many couples and their families.

6.1 Definitions

OII Australia welcomes the Exposure Draft definition of marriage, changing language from “man and woman” to “2 people”. We also welcome other changes in the Exposure Draft, such as changing “a brother and a sister” to “2 siblings”. These changes in language helpfully make no assumptions about legal, biological or individual concepts of sex or gender.

6.2 Existing marriages

We warmly welcome the proposed retrospective recognition of foreign same-sex marriages. This can be expected to benefit large numbers of intersex and non-intersex people.

6.3 Exemptions

As intersex variations are innate, frequently genetic, we do not consider that exemptions should apply on the basis of intersex status, any more than they would apply to any other genetically determined group.

The proposed exemptions permitting religious and civil celebrants to refuse to “solemnise a marriage that is not the union of a man and a woman”[27a] may inadvertently promote discrimination based on appearance and obvious physical characteristics, and not legal classification as man or woman. The proposed exemption may also inappropriately apply to persons who have been coercively classified as a third sex by others, and to persons who have suffered unwanted genital surgeries purported to improve marriageability.

We recall that Australian and international research, both sociological and clinical, shows that intersex people are markedly more likely to change sex classification than the general population, and we are markedly more likely to be same-sex attracted than the general population. We do not believe that intersex persons who are perceived legally or socially as different should be subjected to different standards or exemptions on that basis. Intersex persons who have been othered, or who are perceived to be transgender or who are perceived to be lesbian or gay should not be subjected to different exemptions.

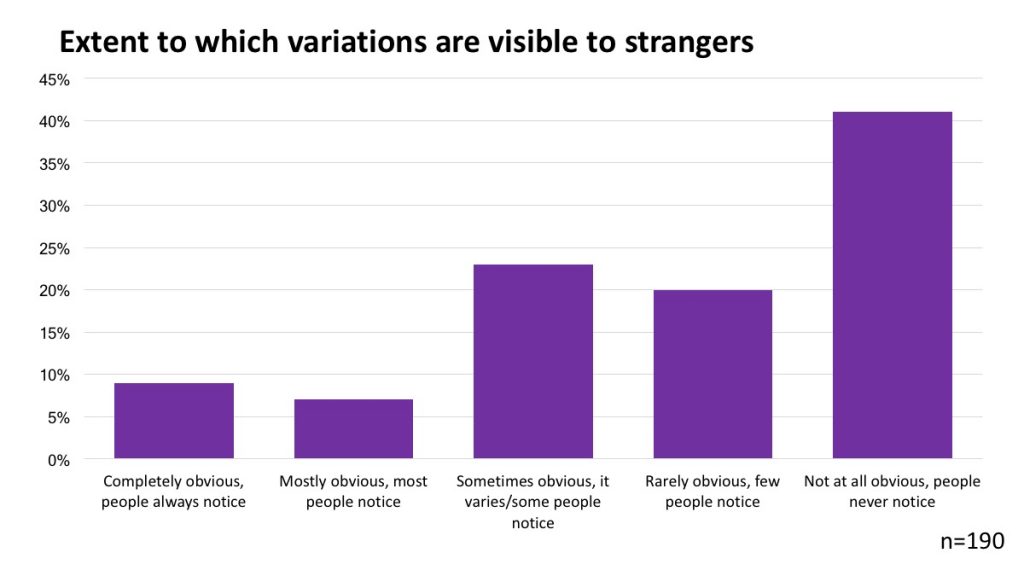

Indeed, those of us who are more obviously different from sex and gender norms are already more likely to be subjected to discrimination. Further, limited public understanding of intersex and frequent conflations of intersex experiences with same-sex attraction and gender transition expose intersex people to such discrimination whether individuals are LGBT or not.

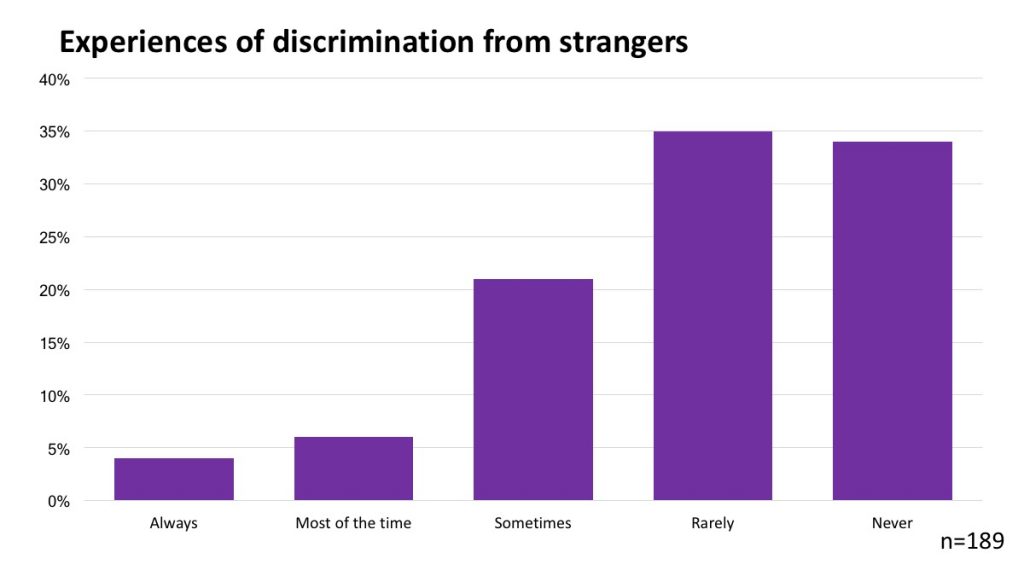

The following two charts, based on information in an Australian sociological study of 272 people born with atypical sex characteristics, shows self-assessed experiences of discrimination and the obviousness of a physical variation to others. These figures show a rough correlation.

Should exemptions be necessary, those exemptions that already apply in the Marriage Act, and in the Sex Discrimination Act, are sufficient to meet the purpose of ensuring that religious celebrants can exercise their own judgement in line with their conscience.

We express our concern about proposals to enable civil celebrants to discriminate on grounds of religious or other conscientious belief. We are also concerned with proposals to enable religious bodies or religious organisations to discriminate where provision of goods, services or facilities are “or the purposes of the solemnisation of a marriage, or for purposes reasonably incidental to the solemnisation of a marriage”.[27b] In our view, these unnecessarily broaden the scope of existing religious exemptions in federal law, and may thus create opportunities for discrimination on the basis that any goods and services may be used in ways incidental to marriage. In our view, such exemptions may create unpredictable consequences.

6.4 Consequential amendments

We believe that, for consistency and the elimination of red tape, the Sex Discrimination Act should be amended to ensure that exemptions applicable to the Marriage Act 1961 no longer apply.

We also note that, because of the current limitation of marriage to a man and a woman, legislation enabling changes in sex classification in several Territories and States prohibits such changes when individuals are married. Marriages may survive such events; this should be welcomed, enabling such marriages to meet their intended aim, voluntarily entered into for life. We recommend that this Bill be amended to eliminate such State/Territory restrictions on marriage. In our view, one single set of principles should apply in Australia.

Unfortunately, in the same way that third sex or gender markers have no impact on harmful clinical practices promoting the so-called “normalisation” of intersex infants, children and adolescents,[28] we do not expect changes to the Marriage Act to have any impact on such practices. Protecting the rights of intersex infants, children and adolescents to bodily autonomy, and creating a coherent policy environment that fully respects our rights, requires specific legislative action.

7. Citation

This paper was written by Morgan Carpenter, co-executive director, in consultation with the board of OII Australia. A suggested citation is:

Carpenter, M, Organisation Intersex International Australia. Submission on the Exposure Draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill. January 2017. Available from: https://oii.org.au/31139/submission-marriage-amendment-2017/

Update: Senate hearing

Morgan Carpenter participated in a Senate hearing in Canberra on 25 January, via teleconference. There are some errors in the proof version of Hansard, but the material is readable.

Hansard transcripts of hearings

References

[1a, 1b, 1c] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Intersex Awareness Day – Wednesday 26 October. End violence and harmful medical practices on intersex children and adults, UN and regional experts urge. 2016 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=20739&LangID=E

[2] Olaf Hiort, 2013, I-03 DSDnet: Formation of an open world-wide network on DSD at clinician conference, “4th I-DSD Symposium”, June 2013: “DSD comprise a heterogeneous group of differences of sex development with at least 40 different entities of which most are genetically determined. An exact diagnosis is lacking in 10 to 80% of the cases”, [cited 1 Jul 2013]. Available from http://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_279274_en.pdf

[3] In an independent Australian study by Jones et al of 272 people born with atypical sex characteristics, 60% of respondents use words including the term intersex; a proportion describe as “having an intersex variation” or “having an intersex condition”. The use of diagnostic labels and sex chromosomes is also common. As is the case for all stigmatised minority populations, language choices vary from person to person, and depending on where used. Only 3% of respondents use the clinical term “disorders of sex development” to describe themselves, while 21% use that term when accessing medical services. This shows a perceived need to disorder ourselves to obtain appropriate medical care. Jones T, Hart B, Carpenter M, Ansara G, Leonard W, Lucke J. Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers; 2016.

[4] United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex. 2015 [cited 5 Sep 2015]. Available from: https://unfe.org/system/unfe-65-Intersex_Factsheet_ENGLISH.pdf

[5] Gillam LH, Hewitt JK, Warne GL. Ethical Principles for the Management of Infants with Disorders of Sex Development. Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 2010;74(6):412–8.

[6] Gillam LH, Hewitt JK, Warne GL. Ethical Principles: An Essential Part of the Process in Disorders of Sex Development Care. Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 2011;76(5):367–8.

[7a, 7b] Australian Senate, Community Affairs References Committee. Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia; 2013.

[8] See current version at: Department of Health & Human Services. Decision-making principles for care of infants, children and adolescents with intersex conditions. 2015 [cited 2016 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/populations/lgbti-health/rainbow-equality/working-with-specific-groups/infants-children-adolescents-with-intersex-conditions

[9a, 9b] Carpenter M. The human rights of intersex people: addressing harmful practices and rhetoric of change. Reproductive Health Matters. 2016;24(47):74–84.

[10] Overington C. Family Court backs parents on removal of gonads from intersex child. The Australian. 2016 Dec 7 [cited 2016 Dec 7]; Available from: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/health-science/family-court-backs-parents-on-removal-of-gonads-from-intersex-child/news-story/60df936c557e2e21707eb198f1300276

Overington C. Carla’s case ignites firestorm among intersex community on need for surgery. The Australian. 2016 Dec 8 [cited 2016 Dec 8]; Available from: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/health/carlas-case-ignites-firestorm-among-intersex-community-on-need-for-surgery/news-story/7b1d478b8c606eaa611471f70c458df0

[11] Copland S. The medical community’s approach to intersex people is still primarily focused on “normalising” surgeries. SBS. [cited 2016 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.sbs.com.au/topics/sexuality/agenda/article/2016/12/15/medical-communitys-approach-intersex-people-still-primarily-focused-normalising

[12] Re: Carla (Medical procedure) [2016] FamCA 7 (20 January 2016); Carpenter M. The Family Court case Re: Carla (Medical procedure) [2016] FamCA 7. OII Australia. 2016 [cited 2016 Dec 7]. Available from: https://oii.org.au/31036/re-carla-family-court/

[13a, 13b] Lee PA, Nordenström A, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, Auchus R, Baratz A, et al. Global Disorders of Sex Development Update since 2006: Perceptions, Approach and Care. Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 2016;85(3):158–180.

[14] Hughes IA. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;91(7):554–63.

[15] Attorney General’s Department. Review of Australia’s Female Genital Mutilation legal framework – Final Report. Attorney General’s Department; 2013 May [cited 2013 May 25]. Available from: http://www.ag.gov.au/Publications/Pages/ReviewofAustraliasFemaleGenitalMutilationlegalframework-FinalReportPublicationandforms.aspx

[16a, 16b] Jones T, Hart B, Carpenter M, Ansara G, Leonard W, Lucke J. Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers; 2016.

[17a, 17b] In the marriage of C and D (falsely called C) (1979) FLC 90-636

[18] Family Court of Australia. Applying for a decree of nullity – Family Court of Australia. 2013 [cited 2017 Jan 7]. Available from: http://www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fcoaweb/reports-and-publications/publications/divorce/applying-for-a-decree-of-nullity

[19] See the sample birth registration form: Australian Capital Territory Government, Office of Regulatory Services. Birth Registration Statement (form 201-BRS). 2014 [cited 2015 Feb 6]. Available from: http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/af/2014-46/current/pdf/2014-46.pdf

[20] Communication by Katy Gallagher, writing as Chief and Health Minister of ACT, to Morgan Carpenter, then president of OII Australia, 15 April 2014.

[21] Communication with Peter Hyndal at the National LGBTI Health Alliance conference, Health in Difference, August 2015.

[22] Communication by Katy Gallagher, writing as Chief and Health Minister of ACT, to Morgan Carpenter, then president of OII Australia, 21 January 2014.

[23] Public statement by the third international intersex forum. Malta; 2013 Dec [cited 2015 Oct 26]. Available from: http://intersexday.org/en/third-international-intersex-forum/

[24] Meyer-Bahlburg HFL. Will Prenatal Hormone Treatment Prevent Homosexuality? Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 1990;1(4):279–83. Nimkarn S, New MI. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1192(1):5–11. Furtado PS, Moraes F, Lago R, Barros LO, Toralles MB, Barroso U. Gender dysphoria associated with disorders of sex development. Nature Reviews Urology. 2012;9:620–7.

[25] Re Kevin: Validity of Marriage of Transsexual [2001] FamCA 1074

[26] New South Wales. Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act, 1995. Available from: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/consol_act/bdamra1995383/

[27a, 27b] Exposure Draft, Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill

[28] Carpenter M. Miraculous thinking. OII Australia. 2016 [cited 2016 Dec 22]. Available from: https://oii.org.au/31093/miraculous-thinking/

You must be logged in to post a comment.