Intersex is not a gender identity, and the implications for legislation

- Read about bodily integrity, and eliminating harmful practices

- Read about eugenics, prenatal screening and elimination

- Read about discrimination, and stigma

- Read about identification documents, sex and gender

Important note: this paper should not be regarded as a guide to our current policy on legislation. Our approaches have been informed by community-building and evidence-building, and are defined (as of March 2017) in the Darlington Statement. For information on data collection, see our page on forms and surveys.

Introduction

Numerous Australian reports have tended to presuppose that intersex people, like gay men, lesbians and transgender people, are included in legal frameworks to protect on the basis of “sexual orientation and gender identity”. This is not the case, and this article attempts to clarify why not.

In brief, people born with intersex variations have many different gender identities; what we share in common is being born with atypical and stigmatised sex characteristics that do not meet stereotypical expectations for men or women. In very many cases, defining intersex as a gender identity misgenders people born with intersex variations: it wrongly treats actual gender identities as invalid or suspect. In some cases, of course, being intersex may also inform an intersex person’s identity.

This article also presents some examples of how intersex people might be protected under anti-discrimination legislation, and recommends use of the term “sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics, or “SOGIESC”.

Intersex people have all sorts of identities: folks from interACT in the US talk with Buzzfeed.

Sex and gender

- Read more on definitions of intersex

- Read demographic data from a 2015 Australian study of 272 people born with atypical sex characteristics

In English, sex and gender describe different concepts, and the word “sex” can also mean many different things. On the one hand, sex may describe biological, physical sex characteristics: a person’s chromosomes, sex organs, and hormones. Statistically, most people are born with characteristics that line up unambiguously in two separate categories, female and male. In the case of intersex people, these traits vary and, because our bodies are seen as different, this exposes us to risks of human rights violations. These risks include risks of forced medical interventions, but also shaming, bullying and stigmatisation because of our physical characteristics and related assumptions about identity.

It’s also important to note that intersex is not an homogeneous singular classification: at least 40 different intersex variations are known to science, and intersex people have many different kinds of bodies, as well as different identities and lived experience. It’s more true to say that intersex people have diverse sex characteristics than talk about intersex as an arbitrary sex. Further, underlying intersex traits may be determined prenatally, at birth, at puberty, or later in life, for example when attempting to conceive a child.

Sex may also simply mean legal sex, the classification that we are allocated or assigned on a birth certificate. In most places, two classifications are available. In a few places, a third classification is available – sometimes associated directly with the existence of intersex people – and the stigma associated with such categories creates complications that appear to increase our risk of human rights violations.

From a medical perspective these risks are that intersex characteristics are routinely surgically and hormonally modified to erase physical differences in an attempt to reinforce a particular sex assignment. From a social and legal perspective, the construction of new third classifications can mean that the actual observed or legal sexes of intersex people are disregarded or called into question.

- Read The “Normalization” of Intersex Bodies and “Othering” of Intersex Identities in Australia by Morgan Carpenter in the Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 2018 →

- Read What do intersex people need from doctors?, an article in the December 2018 issue of the RANZCOG O&G Magazine by Morgan Carpenter →

- Read Intersex surgery disregards children’s human rights, Tony Briffa’s letter to Nature in April 2004 →

Current medical and legal approaches to people born with variations of sex characteristics, are contradictory. Morgan Carpenter (2018) states that:

intersex bodies remain “normalized” or eliminated by medicine, while society and the law “others” intersex identities. That is, medicine constructs intersex bodies as either female or male, while law and society construct intersex identities as neither female nor male.

These contradictions are unfortunately evident in much legislative and regulatory reform in relation to intersex people, both in Australia and internationally.

In contrast, gender describes socially constructed norms about what is appropriate for women or men, and these change over time. Gender norms and gender stereotypes can limit people’s self expression. Gender identity refers to each person’s deeply felt internal and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond with the sex assigned at birth.

Biological sex characteristics, legal sex classifications and gender are likely aligned in most people, but not all. Legal sex classifications and gender are as diverse amongst intersex people as they are amongst endosex (non-intersex) people.

- Read more demographic information from the 2015 Australian study of people born with atypical sex characteristics.

A 2015 Australian study of people born with atypical sex characteristics has given us important demographic information, including data about gender identities, the words people use to describe their sex characteristics, and responses to medicalisation.

The gender of survey respondents

At the time of the survey: 52% of respondents indicated that they were female, 23% indicated that they were male, and 25% selected a variety of other options. Multiple choices were possible.

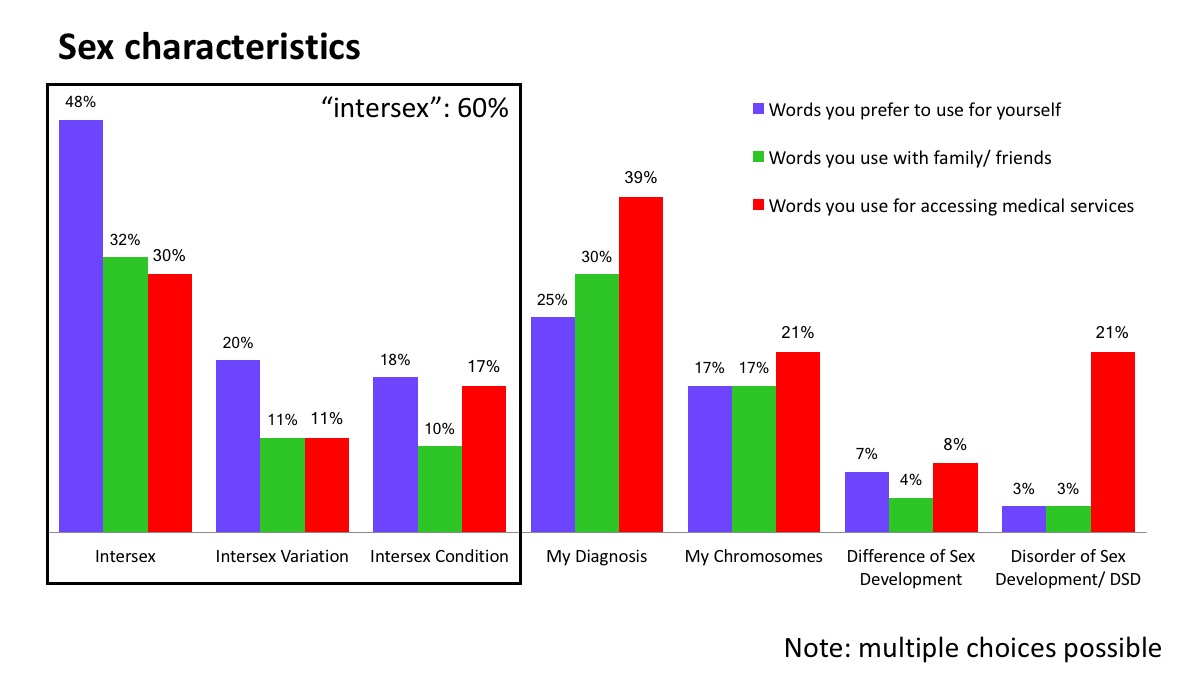

The words people use to describe our bodies and sex characteristics vary significantly. Overall, 60% of respondents use words including the term intersex; a proportion describe as “having an intersex variation” or “having an intersex condition”. The use of diagnostic labels and sex chromosomes is also common.

Sex characteristics

As is the case for all stigmatised minority populations, language choices vary from person to person, and depending on where used. It is particularly notable that only 3% of respondents use the clinical term “disorders of sex development” to describe themselves, while 21% use that term when accessing medical services. From our perspective, this shows a perceived need to disorder ourselves to obtain appropriate medical care.

The Yogyakarta Principles

- Read our statement on the original 2006 Yogyakarta Principles, November 2010.

- Read our statement on the Yogyakarta Principles plus 10, November 2017.

The Yogyakarta Principles “address a broad range of human rights standards and their application to issues of sexual orientation and gender identity”. The original Principles have limited relevance to intersex people because of their focus on these two grounds only – it is our sex characteristics that define us, not our gender identity. Responses to our sex characteristics may be based on fear of our possible gender identity or sexual orientation, but it’s our biological characteristics that needs protection.

The 2017 Yogyakarta Principles plus 10 clarify that sex characteristics are distinct from sex, sexual orientation and gender identity, and that these attributes are intersectional:

UNDERSTANDING ‘sex characteristics’ as each person’s physical features relating to sex, including genitalia and other sexual and reproductive anatomy, chromosomes, hormones, and secondary physical features emerging from puberty; …

RECOGNISING that the needs, characteristics and human rights situations of persons and populations of diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, gender expressions and sex characteristics are distinct from each other;

NOTING that sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics are each distinct and intersectional grounds of discrimination, and that they may be, and commonly are, compounded by discrimination on other grounds including race, ethnicity, indigeneity, sex, gender, language, religion, belief, political or other opinion, nationality, national or social origin, economic and social situation, birth, age, disability, health (including HIV status), migration, marital or family status, being a human rights defender or other status;

The Yogyakarta Principles plus 10 also makes concrete demands regarding protection of the right to bodily integrity, and on legal gender recognition.

Australian states and territories

The NSW, Queensland and Victorian anti-discrimination acts all use near identical wording in their protection of “gender identity” or “transgender persons”.

Section 38A of the NSW Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 No. 48 defines a “transgender person” as who is, or is thought to be, someone:

(a) who identifies as a member of the opposite sex by living, or seeking to live, as a member of the opposite sex, or

(b) who has identified as a member of the opposite sex by living as a member of the opposite sex, or

(c) who, being of indeterminate sex, identifies as a member of a particular sex by living as a member of that sex,

Similarly, the Victorian Human Rights Commission reports:

The Equal Opportunity Act 2010 protects gender identify as a personal characteristic. Under the Act, gender identity is about people of one sex identifying as a member of the other sex, or people of indeterminate sex identifying as a member of a particular sex. People can do this by living, or seeking to live, as a member of a particular sex, or assuming characteristics of a particular sex. This could be through their dress, a name change or medication intervention, such as hormone therapy or surgery.

And in Queensland’s Anti-Discrimination Act 1991, the Schedule Dictionary defines “gender identity as follows:

gender identity, in relation to a person, means that the person–

(a) identifies, or has identified, as a member of the opposite sex by living or seeking to live as a member of that sex; or

(b) is of indeterminate sex and seeks to live as a member of a particular sex.

A casual read might suggest that these provisions would protect intersex people but, in fact, they lack utility.

These legal frameworks fail to protect all people whose innate physical sex characteristics are intersex because they are grounded in the idea that only two narrow and normative sexes are valid: people of “indeterminate sex” are protected essentially only if they are determined, by some authority, to fit norms for a “particular sex”. In doing so, these provisions reinforce coercive medical interventions intended to make intersex bodies fit normative ideas about male and female bodies.

The NSW legislation offers greater protection to “recognised transgender persons” who have recorded an alteration of sex. This simply does not apply to the majority of intersex people who do not ever change legal classification but who still face discrimination because of our sex characteristics. Why anyway should intersex people who have never sought to change sex classification be described as transgender? The definition of what it means to be transgender explicitly proposes a distinction between birth sex assignment and gender identity that does not apply to most intersex people.

The Victorian Equal Opportunity Act 2010 offers protection from discrimination on grounds of “physical features”:

physical features means a person’s height, weight, size or other bodily characteristics;

This attribute may have more relevance and utility to intersex people in that State.

Protecting intersex people from discrimination

Prior to the passing of amendments to the federal Sex Discrimination Act in2013, we identified the following concerns.

Recent federal case law in the US has determined that discrimination on the basis of “gender non-conformity” constitutes sex discrimination (United States Court of Appeals Eleventh Circuit, Glenn v Brumby, No. 10-14833, 10-15015, dated 6 December 2011).

In South Africa, Judicial Matters Amendment Act, 2005 (Act 22 of 2005) amended the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act, 2000 (Act 4 of 2000) to include intersex in its definition of sex:

(a) by the insertion in subsection (1) after the definition of “HIV/AIDS status” of the following definition:

“ ‘intersex’ means a congenital sexual differentiation which is atypical, to whatever degree;”; and

(b) by the insertion in subsection (1) after the definition of “sector” of the following definition:

“ ‘sex’ includes intersex;”.

Finally, the Anti-Discrimination Board of New South Wales has recommended to the federal Attorney General’s Department that intersex people should be protected on the basis of our sex, or sex characteristics:

The Anti-Discrimination Board recommends broad, inclusive coverage of sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics, and gender expression under a Consolidated Federal Act.

Any definition should ensure that it includes variations in sex characteristics, and people who are neither wholly male nor wholly female. In this way people who are intersex, androgynous and other individuals who do not fit within the current binary approach to defining sex would be afforded protection under anti-discrimination law in this context. The Board recommends that broad and inclusive language be used in any definitions of discrimination. In particular, any definition should be wide and inclusive enough to cover people who are intersex without a requirement that any person should identify as either male or female. Discrimination should be prohibited on grounds of actual or perceived sex, sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

In 2011 and 2012, we supported these approaches, and in particular the recommendations of the Anti-Discrimination Board of NSW.

The Sex Discrimination Act, as amended in 2013

- Read our submission to the Senate Inquiry on the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill in December 2012. This bill was later dropped, but the process informed changes to the Sex Discrimination Act.

- Read our submission on the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Bill 2013, April 2013.

- Read our Statement on enactment of this law, June 2013.

“Intersex status” was added to anti-discrimination law, independently of sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation, in 2013. This followed advocacy by us and others. The attribute is defined in the Act as follows:

intersex status means the status of having physical, hormonal or genetic features that are:

(a) neither wholly female nor wholly male; or

(b) a combination of female and male; or

(c) neither female nor male.

The legislative changes resolved many of the issues with failed attempts to include protections for intersex people within attributes protecting on grounds of gender identity, however, the approach taken in federal law has had three failings.

Firstly, it is based on a model of deficit: it makes statements about what intersex lack in relation to typical female and males. Secondly, it has been imputed to mean something about the identity of intersex people, even though the legal attribute refers to physical features. Thirdly, the definition needed to be imprecise to protect people who are perceived to have an intersex variation; for this reason, it is not limited to people born with particular characteristics.

Sex characteristics

- Read our statement welcoming Maltese protections for intersex people, April 2015.

The Australian model has not travelled, internationally.

In Malta a new attribute, introduced in 2015, called “sex characteristics” protects people with intersex variations from discrimination and non-consensual medical interventions. Unlike the Australian attribute of intersex status, this attribute is universal; it deliberately includes everyone. The attribute reads:

“sex characteristics” refers to the chromosomal, gondal and anatomical features of a person, which include primary characteristics such as reproductive organs and genitalia and/or in chromosomal structures and hormones; and secondary characteristics such as muscle mass, hair distribution, breasts and/or structure.

This approach is recommended by the Council of Europe and a growing number of institutions. A version of this definition has been adopted into the Yogyakarta Principles plus 10.

In October 2016, multiple UN and regional human rights institutions issued a joint statement condemning human rights violations on intersex people. As part of that statement, the experts defined intersex in relation to sex characteristics, and called from protection from discrimination on ground of sex characteristics:

Intersex people are born with physical or biological sex characteristics (such as sexual anatomy, reproductive organs, hormonal patterns and/or chromosomal patterns) that do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies. For some intersex people these traits are apparent at birth, while for others they emerge later in life, often at puberty…

States must, as a matter of urgency, prohibit medically unnecessary surgery and procedures on intersex children. They must uphold the autonomy of intersex adults and children and their rights to health, to physical and mental integrity, to live free from violence and harmful practices and to be free from torture and ill-treatment. Intersex children and their parents should be provided with support and counselling, including from peers…

Ending these abuses will also require States to raise awareness of the rights of intersex people, to protect them from discrimination on ground of sex characteristics, including in access to health care, education, employment, sports and in obtaining official documents, as well as special protection when they are deprived of liberty.

We favour the enactment of protections on grounds of sex characteristics.

Most participants at the Darlington retreat. Photo courtesy of Phoebe Hart.

Darlington Statement

The Darlington Statement is a 2017 Australian – Aotearoa/New Zealand intersex community consensus statement. It calls for protection from discrimination on grounds of sex characteristics. The statement also recognises the diversity of the intersex population, acknowledging:

3. The diversity of our sex characteristics and bodies, our identities, sexes, genders, and lived experiences. We also acknowledge intersectionalities with other populations, including same-sex attracted people, trans and gender diverse people, people with disabilities, women, men, and Indigenous – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Tangata Whenua – and racialised, migrant and refugee populations.

4. That the word ‘intersex’, and the intersex human rights movement, belong equally to all people born with variations of sex characteristics, irrespective of our gender identities, genders, legal sex classifications and sexual orientations.

More information

- The Darlington Statement – an Australian – Aotearoa/NZ community consensus statement agreed in March 2017 that includes statements on sex/gender recognition

- Submission on birth certificate reform in Queensland 4 April 2018

- Statement on the Maltese law 2015

This page is periodically updated.

You must be logged in to post a comment.